Introductory Astronomy for Undergraduates

Telescopes

In 1609 an Italian physicist and astronomer named Galileo became the first person to point a telescope skyward. Although that telescope was small and the images fuzzy, Galileo was able to make out mountains and craters on the moon, as well as a ribbon of diffuse light arching across the sky -- which would later be identified as our Milky Way galaxy. After Galileo's and, later, Sir Isaac Newton's time, astronomy flourished as a result of larger and more complex telescopes. With advancing technology, astronomers discovered many faint stars and the calculation of stellar distances. In the 19th century, using a new instrument called a spectroscope, astronomers gathered information about the chemical composition and motions of celestial objects.

Twentieth century astronomers developed bigger and bigger telescopes and, later, specialized instruments that could peer into the distant reaches of space and time. Eventually, enlarging telescopes no longer improved our view… all because of the Earth's atmosphere.

How Telescopes Work (https://cnx.org/contents/LnN76Opl@13.86:fFRziOzt@3/Telescopes)

Telescopes have come a long way since Galileo’s time. Now they tend to be huge devices; the most expensive cost hundreds of millions to billions of dollars. (To provide some reference point, however, keep in mind that just renovating college football stadiums typically costs hundreds of millions of dollars—with the most expensive recent renovation, at Texas A&M University’s Kyle Field, costing $450 million.) The reason astronomers keep building bigger and bigger telescopes is that celestial objects—such as planets, stars, and galaxies—send much more light to Earth than any human eye (with its tiny opening) can catch, and bigger telescopes can detect fainter objects. If you have ever watched the stars with a group of friends, you know that there’s plenty of starlight to go around; each of you can see each of the stars. If a thousand more people were watching, each of them would also catch a bit of each star’s light. Yet, as far as you are concerned, the light not shining into your eye is wasted. It would be great if some of this “wasted” light could also be captured and brought to your eye. This is precisely what a telescope does.

The most important functions of a telescope are (1) to collect the faint light from an astronomical source and (2) to focus all the light into a point or an image. Most objects of interest to astronomers are extremely faint: the more light we can collect, the better we can study such objects. (And remember, even though we are focusing on visible light first, there are many telescopes that collect other kinds of electromagnetic radiation.)

Telescopes that collect visible radiation use a lens or mirror to gather the light. Other types of telescopes may use collecting devices that look very different from the lenses and mirrors with which we are familiar, but they serve the same function. In all types of telescopes, the light-gathering ability is determined by the area of the device acting as the light-gathering “bucket.” Since most telescopes have mirrors or lenses, we can compare their light-gathering power by comparing the apertures, or diameters, of the opening through which light travels or reflects.

The amount of light a telescope can collect increases with the size of the aperture. A telescope with a mirror that is 4 meters in diameter can collect 16 times as much light as a telescope that is 1 meter in diameter. (The diameter is squared because the area of a circle equals πd2/4, where d is the diameter of the circle.)

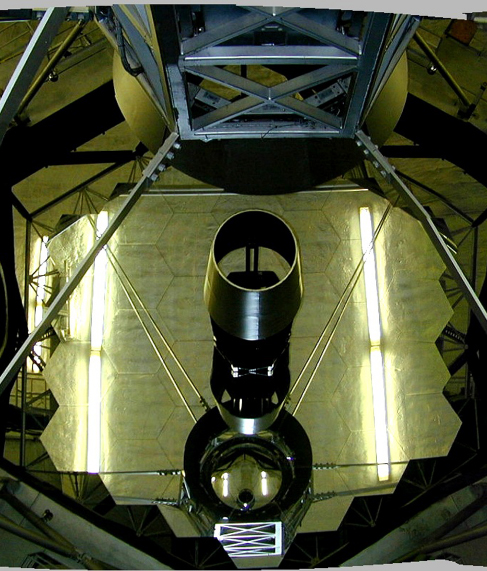

credit: NASA

The mirror of the 10-meter Keck telescope is composed of 36 hexagonal sections. (credit: NASA)

Please visit the following space observatory websites:

http://hubblesite.org/gallery/

http://www.spitzer.caltech.edu/