Writing Is Easier than You Think

This is an in-process draft of McLennan Community College's open-education-resource Composition textbook. Its content is provided freely for use to writing instructors and students. While this book has been developed for use in college-level, freshman-composition courses, if it serves your purposes in any other level of instruction, we are happy to share it with you.

Spinach and Beets (aka The Yucky Stuff)

Overcoming the Red Pen

Let’s get the first thing out of the way first. I understand. You are required to take this course. The college insists that you complete one or two composition courses. But, my decade-plus experience teaching composition courses suggests that most students don’t want to take composition courses.

![Yes, sometimes English class feels lie this.

[PHOTO CREDIT: “Person Holding Red Box” by Pixabay. Pexels, 24 Dec. 2016. CC0.]](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/18216)

Yes, sometimes English class feels like this.

[PHOTO CREDIT: “Person Holding Red Box” by Pixabay. Pexels, 24 Dec. 2016. CC0.]

Yes, sometimes English class feels lie this. [PHOTO CREDIT: “Person Holding Red Box” by Pixabay. Pexels, 24 Dec. 2016. CC0.]

I get it.

You may not be reading this with great joy and anticipation in your heart.

But, writing is easier than you think.

This textbook is designed to support this idea—over and over. Yes, writing requires effort. And, yes, writing takes time. But, if you are willing to work at writing each day (sometimes a little bit, sometime a whole bunch), writing gets easier.

Further, if you are determined to take a new skill and practice it and practice it and practice it, you might be surprised how that skill 1) becomes internalized and 2) becomes flexible and adaptable so that it can become several skills.

Think about a child on a trampoline—and child who is determined to learn to perform front flip. This means to leap into the air, to somersault in mid-air, and to land on your feet. When my daughter was 8 years old, I watched her jump over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over (you get the idea). That child was determined to learn to front flip.

And then after she landed her first successful front flip, can you guess what she did next? That’s right. She attempted it again: over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over.

Click here to watch the jumper's process, to see (and hear) the jumper's success, and to witness the "again-ing." [Video is 57 seconds long.]

When this happens, when success happens, jumping gets easier.

When success happens, writing gets easier.

Some students enter a composition class with a mindset that is set against successes. They’ve internalized the idea that “I’m not a good writer.”

Nonsense! The truth that the student should be saying is “I’ve never been properly encouraged as a writer.” What’s likely true is that the student had a bad English teacher somewhere along the line. This bad English teacher invariable used a red pen and marked errors and errors and errors and errors and errors.

Well, no kidding you think you’re not a good a writer.

If after each attempted front flip on the trampoline my daughter had been met with a voice calling out “Wrong!” or “Fail!” of “Embarrassing!”, she would never have learned to flip. Unfortunately, all that red ink has the same effect. It highlights failure. And who enjoys failure? Who wants to fail over and over and over? Obviously, the answer is that no sane/smart person embraces such negativity.

So, if you are the writing student who—at some point, for whatever reason—stopped trying to flip and flip and flip, let’s start again.

Jumping on a trampoline is easier than you think. And, writing is easier than you think.

But, please don’t merely take my word for it. Malcolm Gladwell, in his book Outliers, proposes a very potent theory of success based on 10,000 hours of practice. He asks whether the great golfer Tiger Woods was simply born a greater golfer than any other golfer of his era. While it is true that there are many factors that must intertwine to establish greatness, Gladwell postulates that an essential/vital/necessary component is the willingness to work at one’s craft: to spend 10,000 hours practicing.

[EXCERPT TK]

Whether this means hitting a golf ball or painting watercolors or front-flipping on a trampoline or writing sentences, true ability and facility with your craft can only be built through determined repletion.

Similarly, Geoff Colvin, in his book Talent Is Overrated, also claims that the key to success isn’t being born great and talents, it’s a combination of skill and luck and most of all persistence.

[EXCERPT TK]

Colvin echoes the girl flipping on the trampoline. Success and talent and skill is all earned by laboring: day after day, jump after jump, sentence after sentence—one builds, one develops, one creates (like a muscle grows over time with repeated exertion) skill and ability.

[TK: Add Anne LaMott’s encouragement from Bird by Bird.]

[TK: Later in this book, multiple drafts of an essay will be connected to Picasso’s 99 sketches. Connect this to Pastor Jett's drafts folder. This can echo the Gladwell/Colvin/LaMott ideas.]

Yet, perhaps more important, and this become a higher-level result, is that will growing skill one relaxes. You’ll be more comfortable writing. You might even—gasp—enjoy writing. And, when this occurs, when you relax and find comfort or solace or even pleasure from writing, writing definitely becomes easier.

Worksheets

Just a Checkmark or a Frowny Face

Pizza Night

Choice

This book, by a willful and deliberate choice on my part, breaks the rules. You will likely have been taught—and I teach my students—that academic writing must be written in the third-person voice. This means that one only writes using he, she, they, it, and (as I did earlier in this sentence) one. If one is writing in this third-person voice, then one would remain consistent and only write in third-person voice.

This is correct and proper academic style. And, with one or two, very few exceptions in this book, all assignments will encourage/require you to write in the academically proper third-person voice.

However, as I stated above, I am going to break rules. I am going to write in first-person voice when it serves my purpose. First-person voice means that I use the words I, me, my, we, and our. Please note, this is one of those examples of “You have to know the rules before you can break the rules.” I know the rules—as do you.

Notice that I just broke another rule. I switched voices, not simply in the same essay, not simply in the same paragraph, but in the same sentence. The previous paragraph ends with the word you. This is second-person voice.

To recap:

First-person is: I, me, (singular); we, our (plural)

Second-person is: you, your (singular and plural)

Third-person is: he, she, it, one (singular); they (plural)

. . . and never the twain shall meet.

Unless they do. In later chapters, this book will present concepts of formal rhetoric and rhetorical analysis. An underlying belief of these chapters is that one becomes a better writer by studying the units (or building blocks) of writing. To wit, one becomes a better writer by studying the writing of other writers. Just as a film student would study the masterworks of auteur filmmakers to help develop his or her own personal style, just as an architect would study the designs from antiquities to understand how load-bearing challenges can be resolved simply, just as rodeo riders talk to other ropers to understand how to more effectively twist-and-rip, so too do writers study the works of other writers. (But, more about this as this book unfolds . . ..)

For our purpose at this moment, let us understand that I may write in the first-person because, as a matter of rhetorical choice (which, simply translated means me trying to make effective writing choices, choices that help my audience grasp my concepts), I might write directly to you.

Effective writers understand, writers who connect with their audiences understand, writers who convey ideas clearly and meaningfully understand—and now you and I understand that writing is about choices.

As we move throughout this book together, exercises and assignments are suggested to help you develop certain skills and to practice certain techniques. This is all toward the goal of helping you become a complete and effective and highly engaging writer. But, just as a soccer coach might emphasize certain footwork drills, just as a basketball coach might perseverate about boxing-out defenders in offensive rebounding situations, just as a singing coach might devote part of every tutoring session to standing properly, just as each of these individual drills and skills is not the complete ability—because soccer is not simply footwork and basketball is not simply rebounding and singing certainly is not simply standing and breathing—just so, one cannot be an effective soccer player without skillful footwork, and one cannot be an effective and complete basketball player without being able to take free balls away from other players, and a slumped and not breathing singer is—well—likely in need of significant medical attention.

The point is: we must develop individual skills so that you can mix-and-match those skills with other skills, as appropriate. You’ll need to fill your tool box with the various implements of your craft so that you be ready to apply a screwdriver or a ratchet wrench or channel-lock pliers, as needed. You’ll collect and define a variety of abilities so that you can kaleidoscope them together, as a particular project requires.

Our approach will be similar to isotonic exercise, developing one muscle, in isolation and in great detail and with rigor, so that it can then, interact with other muscles, which will also be isometrically [CONFIRM TERMINOLOGY with Jerry Mac.] enhanced.

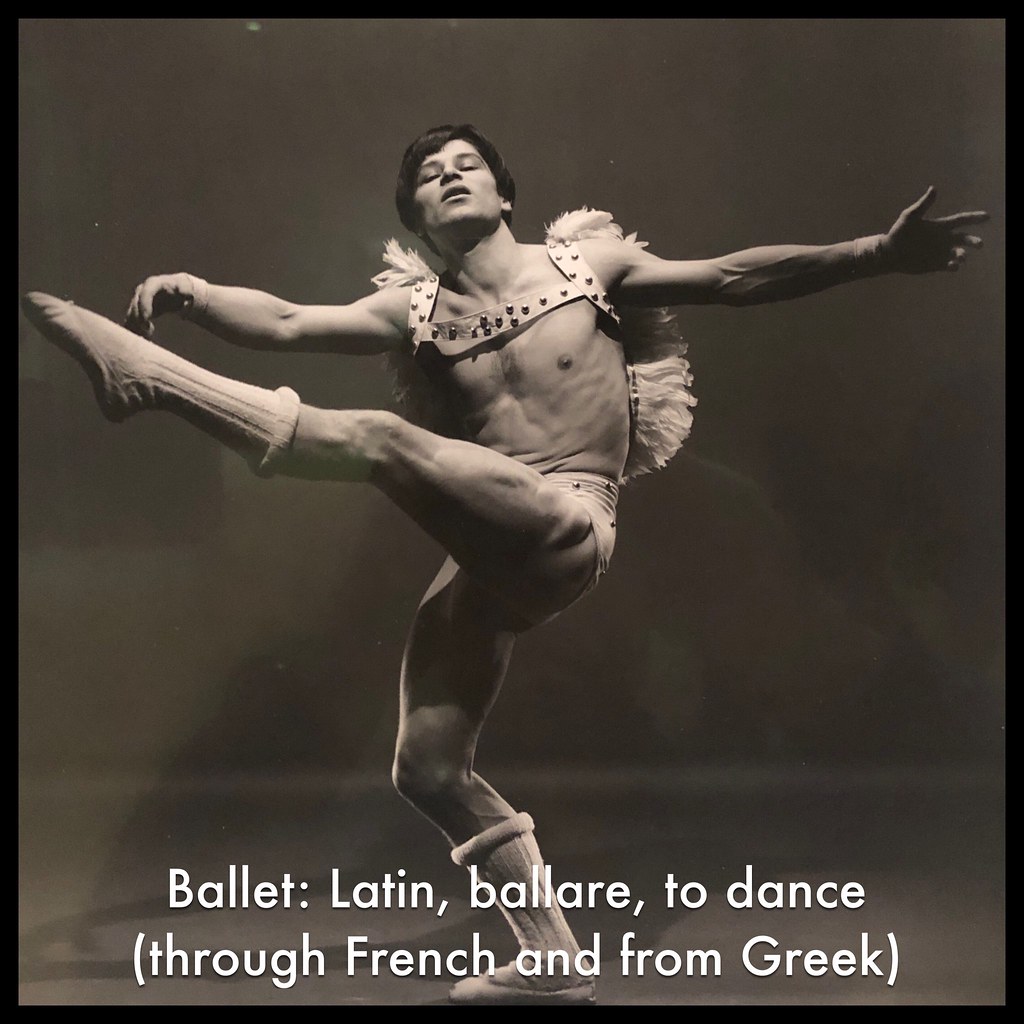

Image a ballet dancer. He stands on one leg with his other leg extended in front of him. His extended leg is held parallel to the floor. That action, alone, requires a great many muscles to work in concert with other muscles—or with opposing tension against other muscles. This one action certainly requires practice—to stand perfectly balanced on one will with the other leg extended forward at a 90 degree angle. Now, imagine adding a new action to the existing action. Imagine that the must flex his toes on the extended foot. The toes had been pointed directly forward as part of the 90 degree angle. But now, the dancer flexes the toes so that they point upward.

If you are in a place where it is appropriate (and

safe) to do so, stand up and try this.

You’ll feel that this new flex, the flexing of the toes upward toward

the ceiling/sky, may tighten muscles in the calf. (Depending on your body awareness, you may

feel other muscles' regions being affected.)

Overall strength, control, and mastery is developed by isolating individual smaller skills/tasks and building those muscles.

[PHOTO CREDIT: "Ballet: Latin, ballare, to dance (through French and from Greek)" by Thomas Talboy is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.]

Overall strength, control, and mastery is developed by isolating individual smaller skills and muscles and opportunities o build those individual strengths. This allows you to hone your craft. "Ballet: Latin, ballare, to dance (through French and from Greek)" by Thomas Talboy is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Note that in flexing the toes upward, we are engaging in a single action, a single gesture. To develop mastery of that single action/gesture, the dancer will flex his toes 10 times, 50 times, 10,000 times. In doing so, the dancer will build a comfort with the toe flex, a confidence about the toe flex, and a well-defined capability to toe-flex when standing on one leg.

This—is writing. This—is any skill. This is, to add one final image, how we learn to swim. Swimming lessons do not begin with swimming. Swimming lessons begin with isolation techniques. A swim instructor isolates one skill for her young polliwogs to practice and develop. It may be that the young (hoping to be) swimmers hold on to a wall and kick their little legs. It may be that they hold their breaths and put their face under water for three seconds. It may be standing on concrete outside the water and wind milling arms through the air.

Just as any skill is learned (be it trampoline jumping, or ballet dancing, or swimming, or fill-in-your-own-blank-here), writing is learned in the exact same manner: with practice, practice, practice.

What follows in this book is a series of practice opportunities. But, that sounds so formal: “Practice Opportunities.” Let’s instead call them play. This about this book like children think about recess. Recess is your chance to run and jump and shout. You can do all that in this book. Recess might also be a time when the teacher channels your play a little bit. Some days might be kickball days. Other days are jump rope days. Some days are swings. Some days are monkey bars. That’s how the chapters will function. One chapter focuses one skill. The next chapter may build upon that skill but do so with a slightly different approach. The next chapter might, perhaps, have a distinctly different approach to writing. (This sudden change is akin to indoor recess on a rainy day.) Yet, when put all together (and your instructor might choose to resequence and/or mix-and-match chapters, this book aims to help you develop your individual skills toward a greater overall facility at, and mastery of, the craft of writing.

CONSIDER: We’ve all heard of the names Picasso, Edison, and Einstein. In many contexts, these names are synonymous with genius, with transcendent, once-in-a-generation talent. However, the great 20th century Spanish painter Pablo Picasso often sketched and drew and painted hundreds of versions of what later became masterworks of art. One such masterwork is “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.” [The image is available on the Internet.]

![How do you get to amazing? Again, and again, and again.

[PHOTO CREDIT: “Man Break Dancing on Street” by Luis Quintero. Pexels, 16 Oct. 2018. CC0.]](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/18215)

How do you get to amazing? Again, and again, and again.

[PHOTO CREDIT: “Man Break Dancing on Street” by Luis Quintero. Pexels, 16 Oct. 2018. CC0.]

How do you get to amazing? Again, and again, and again. [PHOTO CREDIT: “Man Break Dancing on Street” by Luis Quintero. Pexels, 16 Oct. 2018. CC0.]

The Research Paper (Comparative Evaluation)

Overview

Unless you are an English major or unless you major has a dedicated course in writing within your specific discipline, this is likely the final writing course that you will ever take.

Yes. You might be smiling. You might be smiling and nodding. You might be smiling and nodding and waving jazz-hands in the air.

However, that’s why this chapter may be the most important chapter in this book. This chapter assumes that you have had experience with earlier chapters of this book. It also assumes that you have already completed an introductory composition course and that you are reading this in an advanced composition course. Based on these assumptions, you are now ready to learn the truth about the—likely—rest of your academic career.

Tri

The likely truth is that, for the remainder of your academic career (for your undergraduate degree, through grad school, and beyond), it will be assumed that you know how to write. It will be assumed that you know how to research. It will be assumed that you know how to document your sources. It will be assumed that you know how to effectively design a writing project and to structure its form. In short, it will be assumed by your future professors and employers that you know how to write.

And, these same professors and employers will expect to be able to tell you what they expect and for you to be able to deliver that sort of product. It is precisely these assumptions—these expectations by the folks in the future who will control your grades and possibly your salaries—that have driven much of the constrictions on this book. This book has endeavored since its earliest chapters to teach you why it is asking you to structure writing in certain ways. It has striven to provide metacognitive rationales so that you could think about your own process, so that you could consider your readers, so that you could conceive—and reconceive—how to present and idea, how to explore it from many angles, how to construct complexities by developing specific analyses of parts and pieces. In short, this book has been trying to teach you how to build your own products. Notice the plural “products” at the end of the previous sentence. It’s plural because you will have difference purposes for writing projects. You will have different audiences. You will have different tasks within a writing process. All of these variables are sorts of challenges that another professor or employer might throw at you, but possibly with less clarity than you might desire. If this occurs, you’ll be ready.

If your sociology professor or your speech professor or your theatre-history professor throws a writing assignment at you—and doesn’t necessarily provide you much more instruction than “Write a research paper that compares two major influences in X”—you’ll be ready.

Often times, your sociology, speech, and theatre-history professors will state, if challenged, that it’s not their job to teach you how to write a research paper. And, it’s not their job.

If challenged, they’ll claim that you should have been taught research-paper-writing skills in your composition classes. And, you should have been.

If challenged, they’ll content that it’s their jobs to teach you sociology and speech and theatre history. And, they’re right.

If challenged, they’ll suggest that you can get help at the writing center. And, you can.

And that’s why this chapter may be a singularly important chapter not just in this book but in your composition-student experience. Why? Because, after your experience with earlier chapters and previous assignments in this book combined with this chapter’s instructions regarding writing a research paper—you’ll be ready. No matter who the professor or what the task, you’ll be prepared to design and deliver a well-structured, well-researched, and academically persuasive research paper on any subject. When you know a credible form, you can fill it with any content.

This chapter will teach you the form, the shape, that a thoughtful, comparative evaluation can take. As you begin to internalize this form, you can then apply it’s techniques to any discipline. Whether your major is astronomy or zoology or anywhere in between, you be able—with little to no instruction from you astronomy professor or your zoology professor or your anywhere-in-between professors—to craft and to produce a top-flight evaluation.

Objectives

To emphasize the practical nature of this chapter—and to accentuate the urgency of the need for the skills in this chapter—a different approach will be taken from previous chapters in this book. This chapter will proceed with a how-to process, presented as a series of steps or benchmark activities. The rationale behind this is that a complex task cannot be established all at once. A highly integrated product must be built or time. And, as with many works that accomplish high-level goals, an extended timetable is often required. Whether you are afforded three weeks or thirteen weeks to write your research paper, you will need a plan. And, you will need to allow for different metacognitive stages of the writing process ranging from brainstorming and discovery writing, to drafting and crafting outlines and overall shapes for constructions, to collecting and curating sources, to writing sections, to compiling and integrating drafts and sections into a coherent final product, to proofreading before final printing/publishing. There is a sequence to successful writing. This chapter will present a step-by-step sequence, an assignment-by-assignment process, by which you can complete a comparative research paper.

In doing so, by working through and completing this set of steps, you will have internalized a process that you can then carry with you into other classes, into advanced classes, and beyond into you career fields.

When you are told that you need to write a research paper, you can nod. You can nod and smile. You can nod and smile and wave jazz-hands in the air—because you’ve already written a very successful research paper. You already know how.

How does anyone ever learn to do something that’s very challenging? By doing it. This chapter will walk you through that process, the challenging process. And, one the other side, in the next class, when that economics professor begins to describes her research-paper requirements—and as your classmates groan and shake their heads—you’ll nod, smile, and jazz-hands because you’ve been-there/done-that.

The Concept

While not all research papers require a comparison, this chapter will present a comparative research-a-per concept. In doing so, the goal is to provide you with a significant, and complex, challenge. As a result, you will likely stretch more. You’ll need to lift heavier objects. You’ll need to juggle more than one key goals or concept at once. In brief, you’ll be more skillful, more dexterous and agile, as a result. Thus, if you next professor requires a slightly less rigorous paper, then you can scale your efforts down to match those goals. But, if you next professor—possibly a thesis supervisor—presents you with a more rigorous challenge, then you are still closer to those new and elevated expectations because you were challenged with a comparative research-paper evaluation.

The objective for this chapter’s comparative research paper is to compare two things and to evaluate, to judge, to measure, to decide which of the two things is better.

That’s it.

Two things: Which is better?

This framing device of the research question is central to research writing. In a slightly amended version of this assignment, a research question can then lead to a hypothesis. We might envision a botany class. In that class you might be asked to compare and evaluate to soil samples. Of the two soil samples, one might have a higher alkaline content that the other. If so, then a reasonable research question might follow the lines of: which of the two soils (high alkaline vs. low alkaline) will promote faster seedling growth? This is a “Which is better?” research question.

If you were asked to offer a hypothesis, you might predict that one of the two soils will likely produce higher rates of growth. Then, you would conduct an experiment, planting seeds and measuring growth rates of seedlings. When your experiment was complete, you would confirm whether your hypothesis prediction was correct.

Your research paper in this chapter will embrace a version of this same concept. However, you will not offer a hypothesis prediction. Instead, you will simply structure a research questions and then you will collect data that will help you to answer the question.

To affirm. Two things: Which is better?

But, depending on what your two “things” are, the research question of “Which is better?” may not make sense. Sometimes, depending on what your two “things” are, you might want to adjust your research questions to “Which is worse?” For example, is you are evaluating highly destructive hurricanes, for example 1969’s Hurricane Camille vs. 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, the research question “Which was better?” doesn’t make sense. But, asking “Which was worse?” is a meaningful question.

The Challenge

Defining a meaningful research question can present a challenge. If you were simply told to develop a paper that attempts to answer the question of which highly destructive hurricane was the more devastating, you didn’t grow much or stretch much or build many muscle in the effort to design a logic, equitable, and researchable paper. Often, this first step, the choosing of a meaningful comparison to evaluate can take many hours and might involve several wrong turns. However, it is often those students who labor—even struggle—that end up crafts some of the most engaging research papers. Sometimes that effort to truly craft you own design leads to a project that you might end up investing more time and energy and thought into.

To help you toward the goal of developing a meaningful comparison, first, consider the question. You are not asking which is more or which is higher? Those are simple questions. Those are fact questions. It hardly takes a research paper to answer the questions of which hurricane resulted in the greater loss of human life? Or which hurricane cost the most to recover from? Either of these two questions can be answered in a sentence to two.

A question that leads to simple, straightforward, factual answer (a simple, quantifiable answer) is not an effective, evaluative research question. An evaluative research questions, such as which is better or which is worse, then requires that you clarify. How is “better” measured? How is “worse” defined? When you have an evaluative research question of “Which is better?’’ of “Which is worse?”, you then have to provide criteria by which you define and measure better-ness or worse-ness.

Dinner

For example, perhaps you want to take your sweetheart out for a romantic Valentine’s Day dinner. You have two restaurant choice, but, which is better? Well, it depends on how you define “better”? Does “better” simply mean expensive? Or might “better” also entail food quality? What about variety of the menu? Does your sweetheart have special dietary needs or preferences? Does one restaurant have more-romantic ambiance? Will one restaurant have live music playing that night? Does one require complicated travel or parking arrangements?

As you sense, there can be a complex number of judgments, assessments, evaluations, and conflicting choices and demands that go into making a final judgment, a final assessment, a final rendering of a verdict as to why one restaurant is the better choice than another restaurant.

However . . . while the restaurant question is both a comparison and is evaluative, it is not an academically researchable questions. You are unlikely to find scholarly articles written by professors and researchers and scientists and philosophers on your school’s library shelves and within its academic databases that assess the relative merits of dinner at Luigi’s vs. dinner at Cocina Barcelona. While, yes, meaningful to you and your Valentine’s Day aspirations, the which-restaurant question is not academically researchable.

Thus, before you commit to a research paper comparison, consider doing some research. Are there articles on your school library’s databases related to your subjects, related to your possible comparisons? Consider. Is this the sort of thing that serious scholars and professional scientists, and erudite academic would study and publish papers about and take seriously? Do some research. Attempt to find articles. Ask your instructor? Ask the research librarians at your school’s library.

The question of Hurricane Camille vs. Hurricane Katrina is highly researchable. It is studied and written about for meteorological reasons, for humanitarian reasons, for economic reasons, for social planning reasons, for engineering reasons, for predictive-assessment reasons.

For the purposes of this assignment, you will be encouraged to develop your own comparison. But, as you just saw, some examples will be provided that can certainly work for you or can be adapted by you. Coordinate with your instructor about how much choice he or she would like you to enjoy in designing your research paper’s subject.

But, some subjects don’t work. Some subjects, while interesting are not academically researchable. Some subject, whiles seeming that they could be built to work, often don’t pan out very effectively. Some subjects don’t work well because there’s too much opinion/noise about the subject and not enough objective data to explore meaningful analysis.

Allow me to steer you away from subjects that may be interesting—and if we were simply loitering at the local campus coffee shop might be fun to debate—but do not typically serve well for this assignment.

Who’s Better?: Athlete vs. Athlete (such as LeBron James vs. Michael Jordan) OR

Which Is Better?: Sport vs. Sport (such as NFL vs. MLB)

Scholars doesn’t write and publish meaning analysis of King James and MJ in academic journals. Yes, you can read thoughtful writers on ESPN’s website and on Bleacher Report, but we are looking to craft an academic research paper. While the journalists at ESPN and Bleacher report may have degrees from highly reputable journalism schools such as Northwestern, these are not the sorts of source that you want to build your paper on. They can supplement your databases and academic journal sources, but they cannot be a substitute for such sources. And, yes, one can use highly credible non-database sources such as Forbes or The Wall Street Journal to document financial realities of sport vs. sport or athletes as entrepreneurs. But, you are likely trying to start with loopholes and exceptions to amore-traditional research paper. It will serve you better to construct a research-paper product that demonstrates all the hallmarks of strong academic design and research, rather than trying to concoct one, Frankenstein-style that approximates an academic research paper, but upon close examination clearly is not. Fun to talk about, but, no.

Which Is Better?: Phone vs. Phone OR Computer vs. Computer OR Gaming System vs. Gaming System

The trap with these proposals is that you are likely to have the same challenge as the above athlete-vs.-athlete concept, a lack of database sources. But, there is a different—and significant—obstacle with this type of essay. Some/much of the website information you find will be more akin to marketing copy that to actual objective research data. You will have to very actively/aggressively sort out what is content that is produced by the manufacturer to sell its product (ad copy) vs. what is objective assessment. Yes, objective analysts exist (at Consumer Reports or Popular Mechanics etc.), but there are so many websites that may seem to be objective that are simply regurgitating the corporate ad copy. Fun to talk about, but, no.

Which Is Better?: Diet X vs. Diet Y? OR Exercise A vs. Exercise B?

Yes, nutrition science is a legitimate and important field of study. Yes, kinesthesiology or sports medicine might by your major. Yes, there are possible ways to explore a comparison that evaluates dietary choices and/or activity patterns. And, these can be done in very meaningful, even life-altering ways. Without a doubt, properly designing someone’s diet and exercise regimen—and doing it well—could possibly extend his or her life for years. However, for this type of paper to work—and this will be highlighted in later comparison that are showcased as viable options for this assignment—you would need to be more specific, much more specific. (This is a truism for most research paper, but that will be emphasized in subsequent sections of this chapter.) For a diet vs. diet paper to become viable, you’d need to 1) define the specific diet and 2) define the specific dieter. Is this diet for a teenage high school athlete or is it for a 55-year-old person suffering from obesity and type II diabetes? The answer makes a significant difference. Those are two very different dieters; thus, this would become two very different research papers. Similarly, exercise vs. exercise needs to have the specific exercise defines (swimming vs. jogging or Pilates vs. racquetball) and who is doing the exercise (young moms wanting to lose baby weight or senior citizens attempting to forestall muscle atrophy). These sorts of papers can be designed to work, but they do require an extra layer of designing, the creating of a client profile, a “who” that the paper is written for. If the extra work is not done to design a clear client, the paper falls into generalities. Try to avoid.

Guns, Religion, and Abortion – While potent subject to be sure, these subject do not naturally lend themselves to this assignment. The surfeit of emotion and opinion makes culling using data a Herculean labor. Better to preserve these topics for other venues.

Thing X vs. Not Thing X (For example, vaccinating children vs. not vaccinating children). This is an absence comparison. The question that is seemingly being asked is which is better, hamburgers vs. not hamburgers. That’s an X vs. not X comparison; it is not a true X vs. Y comparison. (Hamburgers vs. hot dogs would be X vs. Y.) An absence comparison cannot meaningfully fulfill the requirements of this assignment.

Viable Comparisons

Some comparisons fit very naturally for this assignment. As was the case with specific hurricane vs. specific hurricane, these were significant, even historic, weather events. They have been studied. There is data. The impact of understanding these might help with future weather emergencies. In short, this is a comparison with import. It has meaning; it has relevance; it has importance. It is significant and serious.

This is what you are looking to address. A question with import. However, that does not mean that you have to write about a tragedy. You just have to write about a question that is meaningful to a significant portion of the population.

Roundabout

A student, Jackson, once proposed a comparison that I was skeptical about. I suggested to him that it might lack import. It might not be important enough for people to study and to write about in a meaningful way. But, Jackson was confident. He believed that it was a concept that was taken very seriously by scholars and he assured me that it was “a thing.” So, to make sure that he was proposing a project that would be viable, one that would allow him to be successful with the research paper assignment, I asked him to bring me three academic journal articles about his proposed “thing.”

Jackson arrived at our next class with articles from

the following journals:

- Computers, Environment and Urban Systems

- Accident Analysis and Prevention

- Science of the Total Environment

- Civil Engineering

- International Journal of Sustainable Transportation

- Journal of Advanced Transportation

I was stunned (and delighted). I had no idea that 1) such highly specialized journals existed and 2) that they all had articles about Jackson’s “thing.” Jackson had proposed comparing traffic lights (red, yellow, green traffic lights that you see when driving) vs. roundabouts (those circular events on a road that require you to enter and exit but involve and lights to control the motion of traffic). Jackson wanted to ask the research question: “Which is the more effective traffic-management tool, traffic lights or roundabouts?”

Clearly, this was a subject of import. Highly credible, professional civil engineers, public safety advocates, and transportation scientists took this questions very seriously and seems to write about it and study it extensively.

Jackson had himself a question of import. And, in the end, he produced a stellar

research paper.

To prime the pump for you, following are subjects that work well for this assignment. If one seems to pique your interest, consider researching it more to confirm that this might be a paper for you. Just because it’s a paper of import—and just because it may have worked for a previous student—doesn’t mean it’s an ideal paper for you. This is a project that you might spend 50 days developing. You might spend 75 hours reading and researching and writing. This project should not simply be about a subject of import; it should also—ideally—have import or meaning for you. If you are going to spend 50 days and 75 hours on a project, you should be interested in it. Hopefully it is about something you are interested in—or curious about. Sometimes the challenged is finding that balance and that blend. A subject of import and something that motivates you.

Jackson was motivated by traffic lights and roundabouts. What are you motivated by? What do you want to spend 75 dedicated hours reading about and writing about? This is the first significant challenge that you must master with the research-paper assignment.

Here’s a list of viable comparisons that have worked well for the assignment.

Which is the better green-energy source for the future: wind turbines or solar panels?

(Any number of variants of this paper can also work. The idea is energy source vs. energy source: natural gas vs. coal; OR hydroelectric vs. nuclear; OR wind vs. tidal; OR you get the idea.)

Which is the better therapeutic intervention for Alzheimer’s patients: animal-assisted therapy or music therapy?

(As with the energy vs. energy example above, there are a variety of mix-and-match re-combinations that could work for this subject. For example, light therapy could swap in and replace music OR aroma therapy could swap in and replace animals.)

Other variants of the Alzheimer’s mirror the same structure: what’s the better treatment/therapy for condition K. (Condition K can be just about any physical or cognitive or emotional disorder. K could be depression; K could be cancer; K could be autism; etc.) Depending of the K that is chosen, then the researcher needs to determine what is being compared. (For a K of thyroid cancer, the comparison might be immunotherapy vs. chemotherapy. For a K that is autism, the comparison might be hippotherapy vs. iPad therapy.)

As this chapter unfolds, other viable comparisons will be suggested. You are certainly free to let these ideas inform you and to inspire. But, as has been stated above, a goal of this chapter is to help you choose your own subject, a subject that has meaning for you, a subject with “heat” for you. One that ignites you. One that sparks you curiosity.

Evaluation Criteria

One is a criterion.

Lotsa are criteria.

This is, for some students, a trick vocabulary issue. The singular form, when you have one, is criterion. (Note how the word criterion almost ends with the same letters in the word one.) But, the plural form, when you have one criterion added to one criterion added to one criterion, is lotsa criteria. (I know, I know. Lotsa isn’t really a word, certainly not an academic term that you’d use in your research paper. But, it is used by design to help you hear the plural. The plural of this word ends with a vowel. Just like lotsa ends with an –a, just so criteria ends with an –a.)

To help answer your research questions of which is better (or which is worse depending on the subject that you have chosen to compare), you’ll need to decide: how will you measure better? How will you judge better? What defines/separates better-ness between your two subjects?

These determinants, these tools that you’ll use to measure and to judge, are your evaluation criteria. These evaluation criteria are, ultimately, what will determine the answer to your research question. When we began this chapter, I proposed a question of which restaurant should you take your Valentine’s sweetheart to? As was detailed at that time, you might have lotsa possible criteria. One possible criterion was cost. A different possible criterion was ambiance. A third different criterion was menu items.

Each individual criterion allows you to offer a judgment about the two restaurants. But, when combined, the collective criteria provide you with a series of judgments. The goal of your research paper is to perform this exact operation. By constructing a collection of several criteria, you can apply these criteria to your two subjects to make a final determination about your subjects. You can answer your research questions because you have the data that you have collected from your several criteria.

The Hurricane Camille vs. Hurricane Katrina paper was ultimately judged by criteria. The final answer to the research questions, or which hurricane was the more destructive hurricane was determined by the following criteria:

· Criterion One: The intensity of the storm. This included both wind speeds and rainfall totals.

· Criterion Two: The destructiveness of the storm. This included both human fatalities and property damage.

· Criterion Three: The cost of the storm. This included both lost-revenue during the storms and their aftermaths as well as the rebuilding costs.

In this case, intensity, destructiveness, and cost are the three criteria. As your paper progresses, as you consciously begin to design your paper—and as you continue to read and to research and continue to collect data and impressions—begin to consider what you evaluation criteria will be.

Benchmark Assignment: Identify three possible, academically researchable comparisons. For each of the three possible subjects, also list questions that you believe you'd like to answer in your research paper. Research questions should be phrased to determine the relative value of one subject against the other. Examples of effective research questions (depending on your subjects) could include “Which one is better?”, “Which one has/had/might have a greater impact?”, “Which one is more destructive?” etc.

Also, list at least three evaluation criteria that you might use as measurements to judge the differences between your two subjects. Examples of such measurables (depending on your subjects) could include cost, amount of pollution generated, average income, birth rates, death rates, number of arrests, graduation rates, sales totals, recovery times, recidivism rates, maintenance costs, etc.

Prospectus

After consultation with your instructor (as well as possibly with research librarians or with writing center staff), choose the one proposal for a research paper that you feel most strongly about. Try to choose one that has “heat” for you personally. But, equally meaningful to your decision-making process should be the fact of your proposal being academically researchable. If you have not yet searched for—and found—articles on your library’s databases, then you do not yet have a viable proposal.

The next step to help develop your research paper—and a test that will help you to determine viability—is to write a prospectus. This term, when broken into its prefix and root is:

pro- Something early, something at the start (as in a prologue is the speech or story at the start of a play)

-spectus Related to vision (see the root -spect that is also in our word spectacles, as in eyeglasses)

Thus, a pro-spectus is an early look; it’s a preview.

In your prospectus, consider this opportunity to show off. Fill a page with everything you know. Fill a page with everything that you think is relevant. Fill a page that is even remotely in the ballpark with your idea. Better, fill a page and definitely spill onto a second page. In our use of MLA style, we have by this time internalized the idea that all work that is submitted is double-spaced.

However, in this case, single-space your work. But, do so for very specific reason. By now writing in a single-spaced document, you obviously have to have more to say. This is part of the goal of the prospectus. Say more—and more.

And, if you can’t. If you don’t have enough in your consciousness about this subject, if you don’t have enough just free-floating in your being about this subject already, if you don’t have enough ideas and thoughts and possible evaluation criteria for your two subjects that you are going to compare, if you can’t spill onto a second page when writing single-spaced—then you might not quite have enough “heat” for this subject. A too-short prospectus doesn’t spell the doom of a research paper, but it does suggest that you may not yet have enough knowledge on this subject. You might need to fill your well. You might need to read, read, read more.

Or, you might need to shift to a subject that you have a few more innate ideas about.

For a prospectus, consider this an exercise if very free brainstorming. Just write. Write everything. Don’t judge it. Don’t edit yourself. Allow you research-paper spirit to flow. Perhaps your research paper could include this and it could include that and maybe the other thing might also be part of it too. Write down and record all of these possibilities. In the end, no, of course all of these won’t make their way into the final research paper. But, the goal with early writing, with prospectus writing, is to collect many, many, many possibilities.

Sometimes we shut ourselves down by judging too soon. It is called paralysis through analysis.

Don’t paralyze yourself by overanalyzing yourself. Be free. Write as many ideas as you can that are related to the comparison that you hope/expect to develop into a research paper.

And, if you’ve done some research already. Tell yourself that, too. That’s all part of your process. Record that, also. Tell yourself everything that you think might be happening with your research paper. The sources that you’ve read already are part of this prospectus process. Maybe there are sources that you’d like to read. Mention those. Maybe there’s a documentary film on Netflix you’re planning to watch. Mention that. Maybe you would hope to interview a former teacher of your, or doctor of yours, or somebody else you know who might have some knowledge and expertise and ideas about your research paper subject.

Benchmark Assignment: Your assignment is to create a prospectus that will focus on the one particular subject that you plan to write your research paper about. The most important goal for your prospectus is to "think out loud" or to "brainstorm" as many possibilities as might be relevant to your subject. The more that your prospectus provides, the better it will serve you.

Your prospectus should include the following:

- a statement of the subject;

- several possible research questions;

- a detailing of specific, possible comparisons;

- a detailing of specific, possible topics;

- and a detailing of multiple, likely sources of information and research.

Collecting Research

There are two principal paths that you can follow when conducting research. Both have validity. And each can be used concurrently with the other. One is called Needle-in-the-Haystack. The other is called All-You-Can-Eat Buffet.

Needle

With the Needle-in-the-Haystack approach to research, I am looking for something very specific. For example, if I can comparing wind turbines to solar panels, one of the evaluation criteria that I am planning to examine is cost. How much does it cost to purchase, to ship, and to assemble twenty 300-feet-tall wind turbines?

That is a very specific question and I am looking for a very specific answer (or perhaps several specific answer is shipping costs are different from assembly costs). This is a classic Needle-in-the-Haystack piece of research. I’m looking for that one thing—and only for that one thing. Something this is the easiest form of research. Other times it can be maddening when you believe that the information should be available, but you just can’t seem to find it.

Perhaps this become precisely the moment when you want to pivot to the other form or research. Sometimes you can become too narrowly focused on what you thought was going to be your really, really great idea. But, maybe that really, really great ideas isn’t do great. Maybe it’s a bit of a dead end. Maybe it’s not even really really a thing at all. If so, consider a different approach. Instead, think of research as an All-You-Can-Eat Buffet.

Perhaps you have a favorite All-You-Can-Eat Buffet in your hometown. Or, perhaps you remember a particularly spectular buffet that you ate at on vacation. But, I’m 100% certain that no matter where this buffet is that you are thinking about, when you were there, you put something on your plate that you hadn’t planned to. When you were in the parking lot approaching the restaurant, there may have been some food items that you expected to eat and others that you hoped would be available. But, invariably, there were surprises on the buffet. There were items that you hadn’t thought about. The might have even been things that normally you would never think of as part of that meal, but today for whatever reason, there they were, those surprise items: king crab legs or deviled eggs or minestrone soup or fresh-squeezed limeade. Whatever may have caught your eye or tickled your fancy or suddenly taken you back to something that you haven’t had since your grandmother served it you years ago—you made a discovery. You found a surprise.

Buffet

This can be—even should be—a regular part of your research process. Be open to discovery. Be open to concepts revealing themselves to you as you research. All too often, we are working quickly because we are in a hurry. Perhaps you have to finish that homework assignment for English class before noon, so that you can make it to your work study job, after which you need to squeeze in an hour at the gym before the study group for your chemistry class plans to meet. Oh, yeah. And squeeze in dinner sometime, too. We’re all often very busy. As a result, we may not always budge buffet time into our schedules.

Try, though. Try to schedule research time in which you leisurely stroll through database articles. Take your time reading and exploring. Slow down. Allow yourself to be surprised. Afford yourself the calm to make a new discovery. Let yourself be startled by what you uncover. The All-You-Can-Eat Buffet research technique can produce surprising outcomes. You might develop lines of inquiries that you hadn’t even considered before. You might evolve one evaluation criterion into several because you connected some ideas that you hadn’t connected before. Sometimes the best research work is to simply spend time reasoning, with a specific, needle-like agenda, and without a crisis-like time crunch. Give yourself time and opportunity to looking, to see what else is on the buffet table. Maybe you’ll find a whole new flavor to add to your research paper.

Connecting Research

As you read and research, you are looking for quotations. You are looking for statistics. You are looking for meaningful pieces of information that will help you to present your ideas. The research that you find and collect may, early in the process, feel a bit like individual jigsaw puzzle pieces.

Puzzle

One quote (puzzle piece) seems like it might fit with another quote (anther puzzle piece). One statistic seems to share a similar edge/border as another statistic; they seem to by pieces that work together, fit together to create a more complete images, a more complete idea.

As you are reading and researching, you are looking for pieces of other people’s writing and research that might fit into yours. You will have a unique design. Your research questions may be a bit different from the research question of that article that you are reading. Your audience may be more specialized (or less specialized) than the audience of the article that you are reading.

There will always be some mixing and matching that occurs with the research process and with your actual research paper. You want to, initially, cast you net widely. Find as many puzzle pieces as you can. Collect as many ideas as might relate to your project. In short, put as many puzzle pieces on your work table as possible.

What might end up happening is that you seem to have too many puzzle pieces. This is fine; it might even be desirable. It would be akin to you having puzzle pieces on your table from three or four different puzzles. Ultimately, they don’t all fit together. Ultimately, yes, some of those pieces have to be returned to a different box, discarded, or ignored. But, initially, until you know for sure, allow the jigsaw puzzle that you constructing to possibly grow and develop and progress into some potentially surprising and unexpected ways.

This is the beauty of the research process. You are allowed to build, you are encouraged to explore, and you are free to evolve your ideas based on what you find. Scholars, researchers, academicians, and philosophers have been doing this for millennia. They will consider the ideas that exist. They will examine the work of earlier thinkers, builders, artists, scientists—and then they will recombine those earlier ideas. They will tinker with one part and add it to another part. They might consider exploring the inverse of a well-established idea. They might put together elements in a novel way that hadn’t been previously allowed. For centuries upon centuries upon centuries upon centuries, thinkers have worked with pre-existing ideas and adapted them, stretched them, deconstructed them, and re-built them.

That’s what you, too, are doing. In your research paper, you are collecting the wisdom of others, their research, their quotations, their studies, and their statistics, and then you are combining and re-combining the wisdom and research of many other thinkers into a new shapes and into more unique forms.

As a puzzle, this is both the challenge and the reward of building a research-paper jigsaw puzzle.

You know that the most basic unit of a puzzle is the single piece. You also know that the basic operation of completing a puzzle requires fitting one piece together with one other piece. And, then you repeat. And repeat. And repeat. And you do this as many times as is necessary until all puzzle pieces fit together.

Academic writing, and research writing in particular, is often exactly the same process. When you find one piece, there is often another piece that needs to fit with it. And when you have those two pieces fit together, a third piece also fits together.

For your next assignment related to your research paper, you will be putting pieces together—jigsaw-puzzle style. Other instructors might call this assignment an annotated bibliography—others many have different names for it. Its appellation, however, is not as important as its function.

The functions of this assignment is to get you to start putting pieces together. You are going to take the quotes and the statistics and the other elements of research that you have been finding, and you will connect other pieces to them. As you get the gist of this, you’ll see that the snapping together of these pieces is rather straightforward. But, you will also quickly begin to understand that—little piece by little piece—you are writing small parts of your research paper. This process is analogous to building little sections of a jigsaw puzzle that don’t all fit together yet with all the other parts, but the little section is beginning to grow.

Sailboat

Imagine a large, 2,000 piece jigsaw puzzle of a mountainscape in the background with a lake in the foreground. Above the mountains are shimmering clouds. On the lake is a sailboat. Bordering the lake are the edges of a verdant pine forest. As you begin to spread out these 2,000 puzzle pieces in front of you, you likely organize the pieces a bit. Edge pieces all together. Pine-tree pieces together. Cloud pieces together. The sailboat pieces, definitely together. This is going to be the easiest image to begin to construct. So much of the rest of the puzzle is vastly similar. There’s lots of water. There’s lots of trees. There’s lots of mountain. There’s lots of cloud. But, there’s only one sailboat. So, you might be likely to snap a few of those pieces together first. It might be the first sequence that you begin to complete. It may not yet fit tighter with all of the other parts of the image yet. For now it’s just a few snapped-together pieces that are united amidst a jumble of free and loosely grouped but not-yet-snapped-together cloud pieces and water pieces and leaves pieces.

But, you have snapped together the beginning of the sailboat with three or four pieces now locked into place.

This is the goal of your next assignment. You will take one of your pieces of research and snap a few pieces onto it. In doing so, you are constructing a unit that will very possibly become of completed unity that fits directly into your final research paper.

Think about the small units that you are about to build like a sandwich. The research that you are showcasing (quote, statistic, whatever it may be) is what goes in the middle of your sandwich. Your research is like the meat/cheese/vegetable center of a sandwich. Whatever the center of your sandwich is, that’s what you’re really serving. Well, that what your quotation/statistic is, the center of your research sandwich. But, a sandwich isn’t a sandwich without a top-and-bottom bread/bun. With the top-and-bottom bread/bun, a sandwich isn’t a sandwich; it’s just a sloppy, hard-to-pick-up mess. And you certainly don’t want to serve your reader a sloppy, hard-to-read mess. So, you’ll add two more pieces together to your research.

Built a little research sandwich. Add something before the quote (a top bun) and add something after the quote (a bottom bun). This something-before and something-after structure provides a simple structure to support your quote; it provides a manageable way for your reader to grasp your quote. It makes your quote easier to consume. In short, you’re trying to serve your research in a more accessible way. In an easy-to-manage format. This is the idea that underpins the research sandwich. You are helping your reader to be able to consume your product more readily.

And, when you use this technique consistently, then you further ensure trust from your reader. When you consistently serve a manageable and easy-to-access/easy-to-consume product, you readers want to support your business more, wants to eat more of our food—wants to accept and believe the arguments and evidence that you are providing. The result of a consistent and organized approach to presenting research is that you reader will be persuaded by your professionalism and by the expertise that you are exhibiting.

Sandwich

For the research sandwich, your top bun is a statement of credentials. It’s an announcement of who’s voice is about to be heard. It’s a proclamation that you are delivering expertise. It’s a clarification that you are about to deliver a Gucci product—not just any old source, not just an average source, but a very high-end source, a top-of-the-line source. Tell us, in the top bun part of your research sandwich whose voice we are about to hear in the quote. Where does she teach? Which branch of the military has he served in? Which books has she written? What organization does he lead? Tell us that you are about to give us information for a leader in the field, from someone with solid credential, from someone who certainly should know a great deal, from someone who is clearly authoritative.

If you cannot provide the professional credentials for an actual person, then something the name of the organization can serve as a very appropriate substitute to establish authority. For example, the Union of Concern Scientists, the Harvard School of Public Health, the Mayo Clinic, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are top-flight, Gucci-esque, leaders in their field. These organizations are their own credential. If you are using research from such a strong and highly respected organization, absolutely, announce that as part of your top-bun introduction.

Further, in some instances, where the information was publish can also serve to enrich you presentation of credential. Economic and/or financial data drawn from Forbes magazine or from The Wall Street Journal has an extra ring of credibility. Data and evidence drawn Scientific American or National Geographic or Popular Mechanics may have an extra ring of truth and certainty and validity based on the long-standing reputations of these magazines. The concept here is to rely on sources that follow academically valid methods, that showcase journalistic integrity, and that have a demonstrated track-record of both thoughtful and reliable presentations of evidence.

One reason that this is a particularly impactful technique, even a defining technique for you as an academic writer, is that it announces you as an academic writer with discerning tastes. You do not simply use any old Internet source. You don’t just cite random websites. You are telling your reader that you have hand-selected the best of the best for your reader. You are telling us that you have quality assurance standards and that you are only going to serve us the finest ingredients. By clearly announcing your sources—and establishing their credentials—you are professionally representing yourself as Gucci. You, too, are elevated. You, too, deserve notice. You, too, are discerning and sophisticated.

But, there is another puzzle piece that you need to snap on to complete this unit of your puzzle. There is a bottom bun required to complete your research sandwich.

To perhaps codify this concept, perhaps even excessively underscoring the idea, allow me a moment to suggest that this sandwich technique can also be called the I-I technique (as in the letter I and the letter I). But, typographically, that also seems a bit misleading when typed on the screen. So, allow me to type it as it sounds. The I-I technique is like the eye-eye technique or the aye-aye technique.

Each of these is a mnemonic and each can help solidify this concept into your understanding.

“Eye-eye” suggest “I see, I see.” When you use this sandwich technique, your reader will also see your research very clearly.

“Aye-aye” suggest “Yes, yes.” When you use this sandwich technique, your reader will accept your research much more readily.

“I-I” suggests that you will Introduce and then Interpret.

Introducing is the function of your top bun. Before your let your research be heard, you present why we should listen extra attentively.

Interpreting is the function of your bottom bun. After your research has been shown, help us understand it. Tell us what was particularly significant in the quotation/statistic. Help us to see what you believe was particularly meaningful or provocative or troubling and illuminating in the quotation/statistic.

Don’t just leave it up to your reader to figure it out. Tell us. What was the zinger in that quote/statistic? What were we supposed to “get” loud-and-clearly? Often, this is easier when you have multiple quotations that you are connecting inside a paragraph. When you have multiple pieces of research, your interpretation can compare and contrast the research. Your interpretation can clarify that this quote echoes the claims of a previous quote. Your interpretation can address that this quote actually undercuts an earlier statistic. Your interpretation can accentuate that this quote suggests a whole other focus that may be even more meaningful to explore. Your interpretation, in summation, is the bottom bun of the research sandwich. It is necessary. It is essential. Help us to understand the value of your research. Help us to see the impact of its information. Help us to see how it connect with other ideas, when possible. Certainly help us to see which element in the quotation of the statistic that we should pay the most attention to. By doing so, again, you enhance your own credibility. Your reader will see you as a thoughtful analyst, as a careful critic, and as a reliable tour guide through complex and challenging terrain.

Benchmark Assignment: The assignment is a presentation of three sources that, at this time, seem likely to be included in your research paper. To fulfill this assignment, first state in a single sentence what you are comparing and the research question that you plan to answer. An example might be "Which therapeutic intervention, hippotherapy or augmentative-and-alternative-communication (AAC) applications, is more impactful for children with autism?"

Next, provide a research sandwich for each source (as described above). Your research sandwiched for each source must contain the following:

- a clear attribution that establishes the credentials of the author(s) and/or the publication,

- a direct quote from the source that contains relevant information that you feel will be useful to your research paper,

- an appropriate in-text citation,

- and an interpretation of the quotation. (To avoid redundancy, attempt to suggest what the quote might also mean, what it might also connect to, what it might challenge/contradict, etc.)

- Your assignment must also include a properly formatted works-cited page.

A student named Thy developed a research paper to address the following research “Which packaging, glass or plastic, is more sustainable and healthier to the earth?” Following are several examples of effective, sandwich-style presentations of her research:

According to Morgan Cutolo, an assistant digital managing editor at Reader’s Digest, “Soda in a glass bottle will stay fresher longer because it’s much harder for CO2 to escape through it.” This statement suggests that glass bottle is the best way to preserve the freshness of soda because of it is less permeable to CO2. Glass packaging plays a key role in serving high-quality sodas to the benefit of the consumers.

Lynn Bragg, the President of the Glass Packaging Institute (GPI), affirms that “The first study by the State University of New York in Fredonia as part of a project from the U.S. – based journalism organization Orb Media, found tiny pieces of plastic in more than 90% of samples from the world’s most popular water brands bottled in plastic” (15). The study presented in the quote implies that micro-plastic in bottled water cannot be seen by normal eyes; thus, it possibly can harm the consumers in the long run.

Developing Meaningful Evaluation Criteria—with Subtopics

Now that you are fully immersed in your research paper, you are researching every day, you are finding new articles, reading new chapters of books, watching new documentaries. You are living and breathing your subject in a consistent daily application. As you do this, you will begin to see pattern emerging in what you are reading. You may begin to see consistent areas of study that others cite. You may begin to encounter the same types of evidence, or the same approaches to comparing data sets, or the same focus on certain countries or populations or types of students or dolphins or whatever it is that you are researching about. Depending on what you are researching, your variables will be different, but your experience will be the same. You are now seeing a greater range of complexity than you knew when you started. You are beginning to see more circles, and more overlapping (whether as complementary or as conflicting) circles that define/clarify/challenge your research paper subject and the various ways that you can evaluate it.

This is excellent. This is exactly what you need to have happen.

One cannot simply sit down the night before a research paper is due and craft a thoughtful, meaningful and nuanced research paper. Night-before papers are often shallow. They rely almost excessively on summary. The night-before research paper will read like a report about your subject.

That, most decidedly is NOT what we are writing. We are writing a comparative evaluation to answer a research questions.

To do this, you must be living with your research paper. You must be exploring it and nurturing it and allowing it to transform—over time. Over time, just as the way that a garden grows, the research paper will become different products. Your research paper at this phase is no longer at a prospectus stage. Now you are entering design and outline phase. But, the design and outline phase can only truly—and effectively and meaningfully—be entered into if you have been living in the world of research, breathing research daily, digging your fingers in the research soil each morning and afternoon. If your neck is sunburned and your hands are calloused for all the research digging and exploring that you’ve been doing in the research garden—then you are now ready. Your sunburn and your calluses show that you have labored and that you have nurtured your product. It is now time to finalize your design.

You’ve been exploring and collecting. You’ve been gaining a greater understanding. You’ve been seeing what others write about when they write about this subject. You’ve been building many, many, many little research sandwiches and setting them aside. These little units, these jigsaw-puzzle sailboats are ready to start being combined with other elements of your puzzle. It’s time to define the full shape that you expect to achieve. And, once this is done, then you can start putting all the pieces, all the sailboats, all the sandwiches, into their proper places, into a meaningful relationship with the others sailboats and sandwiches so that you can achieve a coherent, cogent, and complete jigsaw puzzle—so that you can deliver a scholarly and engaging research paper.

The next step it to define the sequence of your evaluation.

If we are going to evaluate, if we are going to judge, if we are going to make decisions as to why one option is better than another (as the student named Thy was attempting to do in the above examples of research sandwiches), we need to clearly define the criteria that will allow us to make thoughtful and definitive judgments and decisions.

But, we also need to consider complexity and thoroughness. We need criteria that are not simple and one dimensional. This does not serve your purpose. They offer a glib and overly reductive assessment that undercuts you. You don’t want to short-change your reader by offering a quick and facile account. Instead, you want to spend time to build a detailed and multipart analysis. This is the difference between inconsequential work and noteworthy work.

When you produce evaluations in the following form, it will garner attention. In doing so, you will also garner attention.

Unicycle

As has been presented in earlier chapters [TK: Add cross-reference to Argument chapter.], a unicycle is a wobbly mode of transportation. It is inherently unstable because it only has a single point of contact with the ground. We are going to re-introduce the imperative to avoid unicycling. Your research paper certainly aspires to strength and stability. In no way do we want to allow for wobbly and unstable assessments.

Thus, we’ll build a 3x2 support structure of your research paper’s evaluation. You’ll develop three unique and separate criteria by which to measure and judge your two subjects. And—each of these three will be structured upon two subtopics.

Consider the following:

Thy is planning to compare glass packaging and plastic packaging. Here research question, as was presented above, is “Which packaging, glass or plastic, is more sustainable and healthier to the earth?” After sustained reading and research, she determined that the following would serve her well—because they made sense to help answer her questions AND because there was support for and evidence related to these criteria in the available research that she had been doing.

The many little research sandwiches that she had collected helped her to understand that the following criteria would serve quite effectively to help her answer her research question.

- Criterion One: Cost. Cost will be further divided into two subtopics: cost of materials and cost for transportation.

- Criterion Two: Environmental impacts. This criterion will be broken down into two subtopics: recycling/sustainability and landfills.

- Criterion Three: Consumers’ benefits. This will be further divided into two subtopics: safety and quality.

She believed that these three criteria (cost, environmental impact, and benefit to consumers) were three meaningful assessments. She believed that these would each allow her offer a reasoned and comparative study of both of her subject (glass packaging and plastic packaging). That is to say, cost is relevant to answering the research question of “Which is better?” Environmental impact is also relevant to why one might be considered better than the other. And, certainly, benefit to consumers also makes sense when judging why one might be preferable to the other.

But, notice that each of these three criteria (cost, environmental impact, and consumer benefit) will be presented from two different angles. Each criterion will be developed via two subtopics. Such a subtopic structure will present strength and stability to the assessment. It will also help to convince your reader by presenting depth of analysis. This subtopic structure—this deeper dive into each evaluation criterion—allows you to present a more-complete picture of your subjects, and to provide more points of contrast so that—ultimately—your judgments in more effectively informed because more considerations were integrating into your decision-making process.

To be clear, this will likely prove to be a challenging aspect of your research paper—possibly a very challenging aspect of your research paper. Trying to determine meaningful subtopics can take time and will require thought. Since it can be a demanding—an may even be a frustrating process—I want to present several examples to help you see how you can approach the task of designing subtopics that are relevant to the criterion but that will also help you to be successful at extracting thoughtful points of analysis by which you can expand the depth of your evaluations.

First let’s look at Thy’s choices. When she designed her first criterion, she determined that cost might have two different meanings or two different applications. First, there is cost to make the glass and plastic bottles. Second, there is the cost to transport the glass and plastic bottles. These are certainly two different aspects of cost. And, she believed that she had collected data (or could likely find data) that would addressed costs to make and—separately—cost to move. Thus, she determined that manufacturing costs and transportation costs were to different, but relevant, subtopics of cost. She believed that these would all her to speak thoughtfully, and more completely, about a fullness of costs associated with glass and plastic packaging concerns.

Her next evaluation criterion was environmental impact. For her subtopics, she decided that she might approach this with a kind of before-and-after concept. She proposed to examine both how effectively the products can be recycled and also how harmful the product are once they are not recycles. So, her subtopics focused on recycling sustainability and landfill impact. With the first subtopic, she proposed to explore the ease with which consumers can recycle as well as how much municipal support is needed. With the second subtopic, she proposed to document how damaging the items are to soil, water, and air resources if they are left to rot in a landfill.

With this second criterion, Thy may have forced together two subtopics that are not such an obvious pairing as her two cost subtopics. While these environmental impact subtopics may not share such an obvious alignment with each other, Thy ultimately made a convincing argument in her research paper as to why both of these subtopics were clearly relevant to her overall research question—and how they did suggest echoes of each other. That is to say, she offered cogent rational for why these subtopics truly belonged in her paper, and how they did inform the criterion of environmental impact. The relation was a causal one. If subtopic A (recycling) failed, then subtopic B (landfills) became more significant as an environmental concern.

Thy’s final evaluation criterion focused on benefits to consumers. Her subtopics were the safety of consumers’ experiences and the quality of consumers’ experiences with glass bottles and with plastic bottles. She proposed that the first subtopic would focus on whether the glass or plastic might shed little bits glass or plastic into the product, thus forcing consumers to drink or eat little bits of glass or plastic. Her second subtopic planned to evaluate whether the quality of the drink/food item (the flavor, texture, or chemical composition) could be affected by the glass or plastic. This may have been one of Thy’s most clearly aligned pairs of subtopics. Under the criterion of consumer benefit, the subtopics of will it damage me and will it damage my drink/food absolutely support has a direct and likely immediate impact on consumers and their experience.

As a final note about design and structure, think back to Thy’s three evaluation criteria. It is not an accident that she presented them in the order that she did. She chose her sequence of criteria quite deliberately. She deliberately placed the benefit-to-consumer criterion last. She did so for emphasis. She wanted to finish with a flourish. She wanted to end with a bang. She wanted to walk-off with a “Wow.” Yes, cost is one thing that is relevant, and sustainability and biodegradability concerns do matter, but will these products ruin your food and possibly poison you!?—that’s something else entirely. That is a final knock-out blow. Stylistically, Thy wanted to build toward this final, most-dramatic-of-all type of evaluation criterion as her final assessment.

Consider. What’s the optimal sequence for your evaluation criteria? Which one to you want to start with? Which do you want to finish with? The order that you present these in might make a difference. Perhaps one criterion lays the foundation for the next one. Perhaps there is a sequential or causal relationship that matters—or is even necessary. But, as Thy did, you can also consider dramatic effect? Do you start with your most-dramatic content to start your paper? Depending on your paper, you could. Or, do you build toward the drama and save the most-of-all for the end. This is a qualitative decision that you will need to make based on your specific paper and the content that you are presenting.

Now that you’ve read through Thy’s criteria and subtopics with my explanations and overlays. Allow me to get out of the way. Below are numerous research questions, evaluations criteria, and subtopics that previous students developed into highly effective and engaging research papers.