Apartheid Primary Sources

What Life Was Like In South Africa During Apartheid

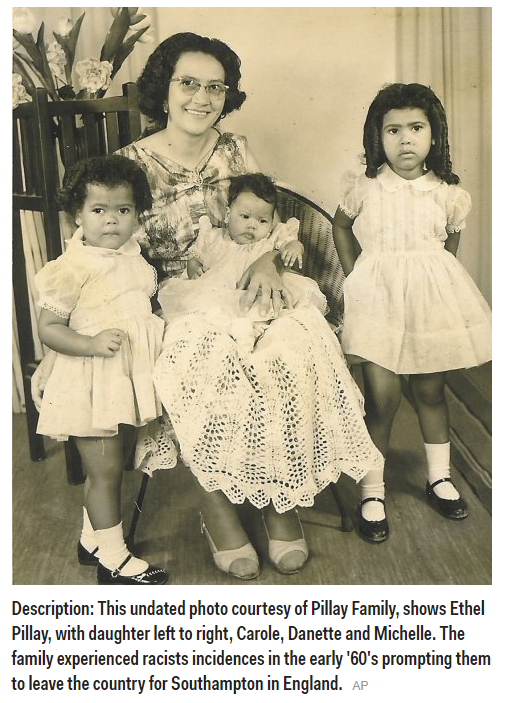

By: Michelle Faul, Associated Press, Dec. 9, 2013

JOHANNESBURG (AP) — My mother was furious. The operators of the gas station in rural, racist South Africa had taken her money to fill the car, but would not give her the key to the toilets. They were for whites only.

It was the early 1960s, and apartheid was the law of the land.

So my indomitable mum did the only thing she could do: She ordered me and my two sisters to urinate right there, very publicly, in front of the fuel pumps.

We did not disobey, but I started crying — and my sisters bawled, too. We lowered our shorts, but I was so traumatized that I simply could not go.

We had been on the road for more than 15 hours that day. We were taking the car because the train ride was difficult for a woman with three children and lots of baggage.

The train also was an uncomfortable ride for blacks: Halfway through the trip, in the middle of the night, they would have to get out of the Rhodesian Railways compartments and transfer to decrepit blacks-only South African carriages.

The car trip presented its own challenges. Hotels catered only to whites, so the drive needed to be nonstop. We also had to carry piles of food and drinks because my mother refused to go to the back door of shops; only whites were allowed inside the stores.

We moved to England from Rhodesia when I was child because my mother fell in love with a white man, Michael Faul, who had come to Rhodesia when he was 2. His mother strenuously objected to the marriage, and for years, she was estranged from her only son until my mother forced him to reconcile.

I remember our ship docking in Southampton. On the train ride to London, seeing whites doing menial work, I exclaimed to my mother: "But those are Europeans — picking up dustbins!" It was so alien.

On subsequent visits to South Africa as a teenager, I had a British passport. That put me in the peculiar position of being an "honorary white" — meaning I could stay in white hotels and, upon showing my passport, go to restaurants, movie theaters and other places reserved for whites. The exception was South Africa's racially segregated beaches.

To my surprise, I realized that Johannesburg was not made up of dusty, treeless suburbs with poor homes crowded onto small plots overlooked by dumps. White people lived in green neighborhoods with paved roads and sidewalks, in lush homes with gardens, swimming pools and tennis courts.

When that evil system finally was crushed, we all were in awe of Mandela's insistence on reconciliation and not retribution. It is a tribute to him that today, as he ordained, I and others forgive but do not forget.

EDITOR'S NOTE — Michelle Faul is Chief Africa Correspondent for The Associated Press.

Second letter from Nelson Mandela to Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd (June 26, 1961)

I REFER YOU TO MY LETTER of 20 April 1961, to which you do not have the courtesy to reply or acknowledge receipt. In the letter referred to above I informed you of the resolutions passed by the African National Conference in Pietermaritzburg on 26 March 1961, demanding the calling by your Government before 31 May 1961 of a multi-racial and sovereign National Convention to draw up a new non- racial and democratic Constitution for South Africa.

The Conference Resolution which was attached to my letter indicated that if your Government did not call this Convention by the specific date, country-wide demonstrations would be staged to mark our protest against the White Republic forcibly imposed on us by a minority. The Resolution further indicated that in addition to the demonstrations, the African people would be called upon not to co- operate with the Republican Government, or with any Government based on force.

As your Government did not respond to our demands, the African National Council, which was entrusted by the Conference with the task of implementing its resolutions, called for a General Strike on the 29th, 30th and 31 st of last month. As predicted in my letter of 20 April 1961, your Government sought to suppress the strike by force. You rushed a special law in Parliament authorising the detention without trial of people connected with the organisation of the strike. The army was mobilised and European civilians armed. More than ten thousand innocent Africans were arrested under the pass laws and meetings banned throughout the country.

Long before the factory gates were opened on Monday, 29 May 1961, senior police officers and Nationalist South Africans spread a deliberate falsehood and announced that the strike had failed. All these measures failed to break the strike and our people stood up magnificently and gave us solid and substantial support. Factory and office workers, businessmen in town and country, students in university colleges, in the primary and secondary schools, rose to the occasion and recorded in clear terms their opposition to the Republic.

The Government is guilty of self-deception if they say that non-Europeans did not respond to the call. Considerations of honesty demand of your Government to realise that the African people who constitute four-fifths of the country's population are against your Republic. As indicated above, the Pietermaritzburg resolution provided that in addition to the country-wide demonstrations, the African people would refuse to co-operate with the Republic or any form of government based on force.

Failure by your Government to call the Convention makes it imperative for us to launch a full-scale and country-wide campaign for non-co-operation with your Government. There are two alternatives before you. Either you accede to our demands and call a National Convention of all South Africans to draw up a democratic Constitution, which will end the frightful policies of racial oppression pursued by your Government. By pursuing this course and abandoning the repressive and dangerous policies of your Government, you may still save our country from economic dislocation and ruin and from civil strife and bitterness.

Alternatively, you may choose to persist with the present policies which are cruel and dishonest and which are opposed by millions of people here and abroad. For our own part, we wish to make it perfectly clear that we shall never cease to fight against repression and injustice, and we are resuming active opposition against your regime. In taking this decision we must again stress that we have no illusions of the serious implications of our decision.

We know that your Government will once again unleash all its fury and barbarity to persecute the African people. But as the result of the last strike has proved, no power on earth can stop an oppressed people, determined to win their freedom. History punishes those who resort to force and fraud to suppress the claims and legitimate aspirations of the majority of the country's citizens.

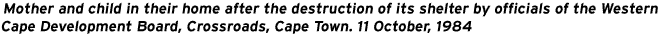

Mother and Child in their home after destruction...

Photographer: David Goldblatt

The shelter was a framework of brushwood staked into the loose sand of the Cape Flats and covered by plastic sheets--black plastic near the base for privacy, translucent plastic over the roof for light. Neatly, without touching the contents of the home or its occupants, a team of five Black men, supervised by an armed White, lifted the entire structure of frame and plastic skin off the ground and placed it nearby. Then they pulled off the plastic, smashed the framework and threw the pieces onto a waiting truck. Hardly a word was spoken. While they could legally destroy the wooden framework, they were forbidden, by the quirk of a court decision brought against the State seeking to prevent these demolitions, from confiscating or destroying the plastic. So it was left where it fell.

Then the convoy--a police Landrover, the truck with the demolition squad and broken wood, and a Casspir with policemen in camouflage lolling in its armored back--moved towards the next group of shelters.

For a while the woman lay with the child. Then she got up and began to cut and strip the branches of Port Jackson bush to make a new framework for her house. The child slept.

Source: https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/1998/goldblatt/capetown.html

An apartheid law: Population Registration Act of 1950

The Population Registration Act No. 30 (commenced on July 7) was passed in 1950 and it defined in clear terms who belonged to a particular race. Race was defined by physical appearance and the act required people to be identified and registered from birth as belonging to one of four distinct racial groups: White, Coloured, Bantu (Black African) and other. It was one of the "pillars" of Apartheid. When the law was implemented, citizens were issued identity documents and race was reflected by the individual's Identity Number.

The Act was typified by humiliating tests which determined race through perceived linguistic and/or physical characteristics. The wording of the Act was imprecise, but it was applied with great enthusiasm:

"A White person is one who is in appearance obviously white – and not generally accepted as Coloured – or who is generally accepted as White – and is not obviously Non-White, provided that a person shall not be classified as a White person if one of his natural parents has been classified as a Coloured person or a Bantu..."

"A Bantu is a person who is, or is generally accepted as, a member of any aboriginal race or tribe of Africa..."

“Coloured person” means a person who is not a white person or a native…”

POPULATION REGISTRATION ACT NO. 30: RACIAL TEST

The following elements were used for determining the Coloreds from the Whites:

- Skin color

- Facial features

- Characteristics of the person's hair on their head

- Characteristics of the person's other hair

- Home language and the knowledge of Afrikaans

- Area where the person lives

- The person's friends

- Eating and drinking habits

- Employment

- Socioeconomic status

THE PENCIL TEST

If the authorities doubted the color of someone's skin, they would use a "pencil in hair test." A pencil was pushed in the hair, and if it remained in place without dropping, the hair was designated as frizzy hair and the person would then be classified as colored.

If the pencil dropped out of the hair, the person would be deemed white.

INCORRECT DETERMINATION

Many decisions were wrong, and families wound up being split and or evicted for living in the wrong area. Hundreds of colored families were reclassified as white and in a handful of instances, Afrikaners were designated as colored. In addition, some Afrikaner parents abandoned children with frizzy hair or children with dark skin who were considered outcasts by the staunch parents.