Chapter 19 - Social Revolution

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” Martin Luther King Jr., 1963

Total Video (01:66:38)

RECONSTRUCTION COMPLETED?

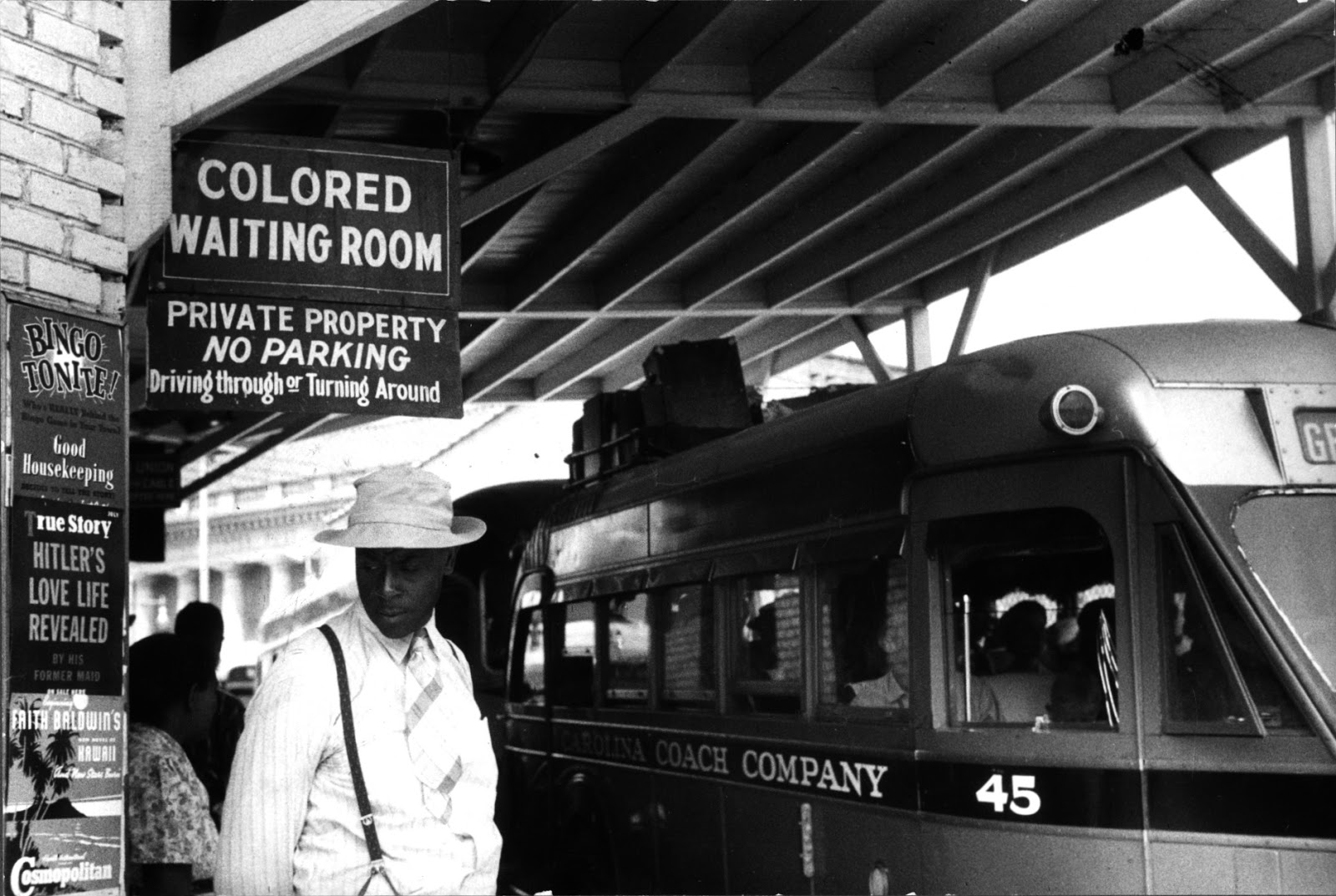

The Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s would, arguably, complete what Reconstruction had failed to accomplish nearly a century earlier. When Reconstruction abruptly ended in 1877, southern states immediately passed “Jim Crow” laws which mandated the separation of the races, especially in regards to public facilities and accommodations.

African Americans became increasingly restive in the postwar years. During the war they had challenged discrimination in the military services and in the workforce, and they had made limited gains. Millions of African Americans had left Southern farms for Northern cities, where they hoped to find better jobs. They found instead crowded conditions in urban slums. Now, African-American servicemen returned home, many intent on rejecting second-class citizenship.

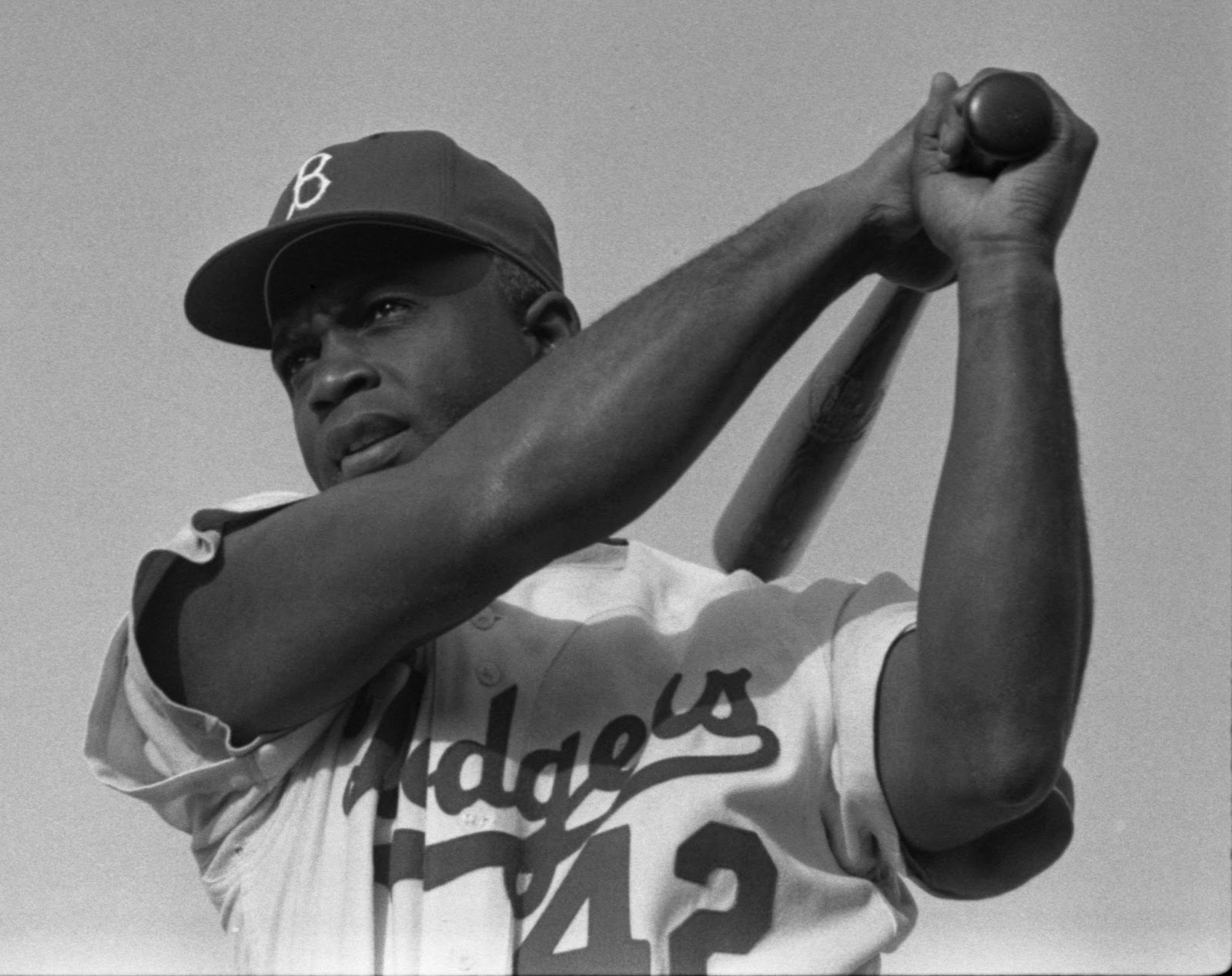

Jackie Robinson dramatized the racial question in 1947 when he broke baseball’s color line and began playing in the major leagues. A member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he often faced trouble with opponents and teammates as well. But an outstanding first season led to his acceptance and eased the way for other African-American players, who now left the Negro leagues to which they had been confined.

Government officials, and many other Americans, discovered the connection between racial problems and Cold War politics. As the leader of the free world, the United States sought support in Africa and Asia. Discrimination at home impeded the effort to win friends and influence enemies in other parts of the world.

The Federal Government Supports Desegregation

Harry Truman supported the early civil rights movement. He personally believed in political equality, though not in social equality, and recognized the growing importance of the African-American urban vote. When apprised in 1946 of a spate of lynchings and anti-black violence in the South, he appointed a committee on civil rights to investigate discrimination. Its report, To Secure These Rights, issued the next year, documented African Americans’ second-class status in American life and recommended numerous federal measures to secure the rights guaranteed to all citizens.

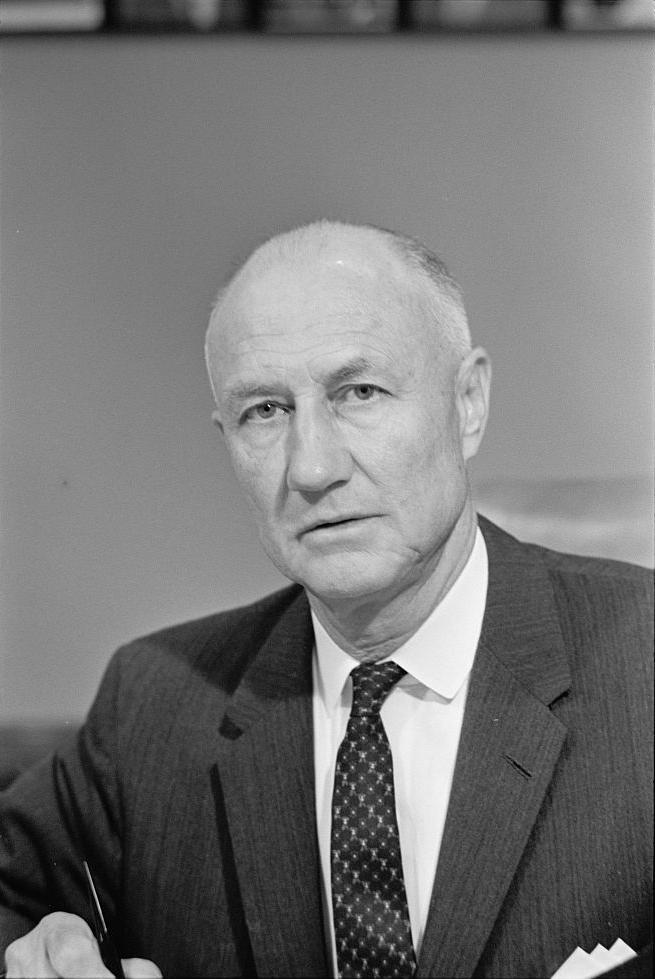

Truman responded by sending a 10-point civil rights program to Congress. Southern Democrats in Congress were able to block its enactment. A number of the angriest, led by Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, formed a States Rights Party to oppose the president in 1948. Truman thereupon issued an executive order barring discrimination in federal employment, ordered equal treatment in the armed forces, and appointed a committee to work toward an end to military segregation, which was largely ended during the Korean War.

African Americans in the South in the 1950s still enjoyed few, if any, civil and political rights. In general, they could not vote. Those who tried to register faced the likelihood of beatings, loss of job, loss of credit, or eviction from their land. Occasional lynchings still occurred. Jim Crow laws enforced segregation of the races in streetcars, trains, hotels, restaurants, hospitals, recreational facilities, and employment.

DESEGREGATION

Video (00:03:38) Civil Rights Beginnings (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=47585&loid=411511)

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took the lead in efforts to overturn the judicial doctrine, established in the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, that segregation of African-American and white students was constitutional if facilities were “separate but equal.” That decree had been used for decades to sanction rigid segregation in all aspects of Southern life, where facilities were seldom, if ever, equal.

Brown v. Board of Education

African Americans achieved their goal of overturning Plessy in 1954 when the Supreme Court — presided over by an Eisenhower appointee, Chief Justice Earl Warren — handed down its Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Thurgood Marshall argued successfully before the Court in Brown v. Board of Education that Linda Brown (a black schoolgirl) was stamped as inferior in her own mind, and the minds of others, by having to walk past a white school to attend a black school farther away.The Court declared unanimously that “separate facilities are inherently unequal,” and decreed that the “separate but equal” doctrine could no longer be used in public schools. A year later, the Supreme Court demanded that local school boards move “with all deliberate speed” to implement the decision. This ruling undid the “separate but equal” ruling of 1896 but the real challenge would be enforcement.

Little Rock

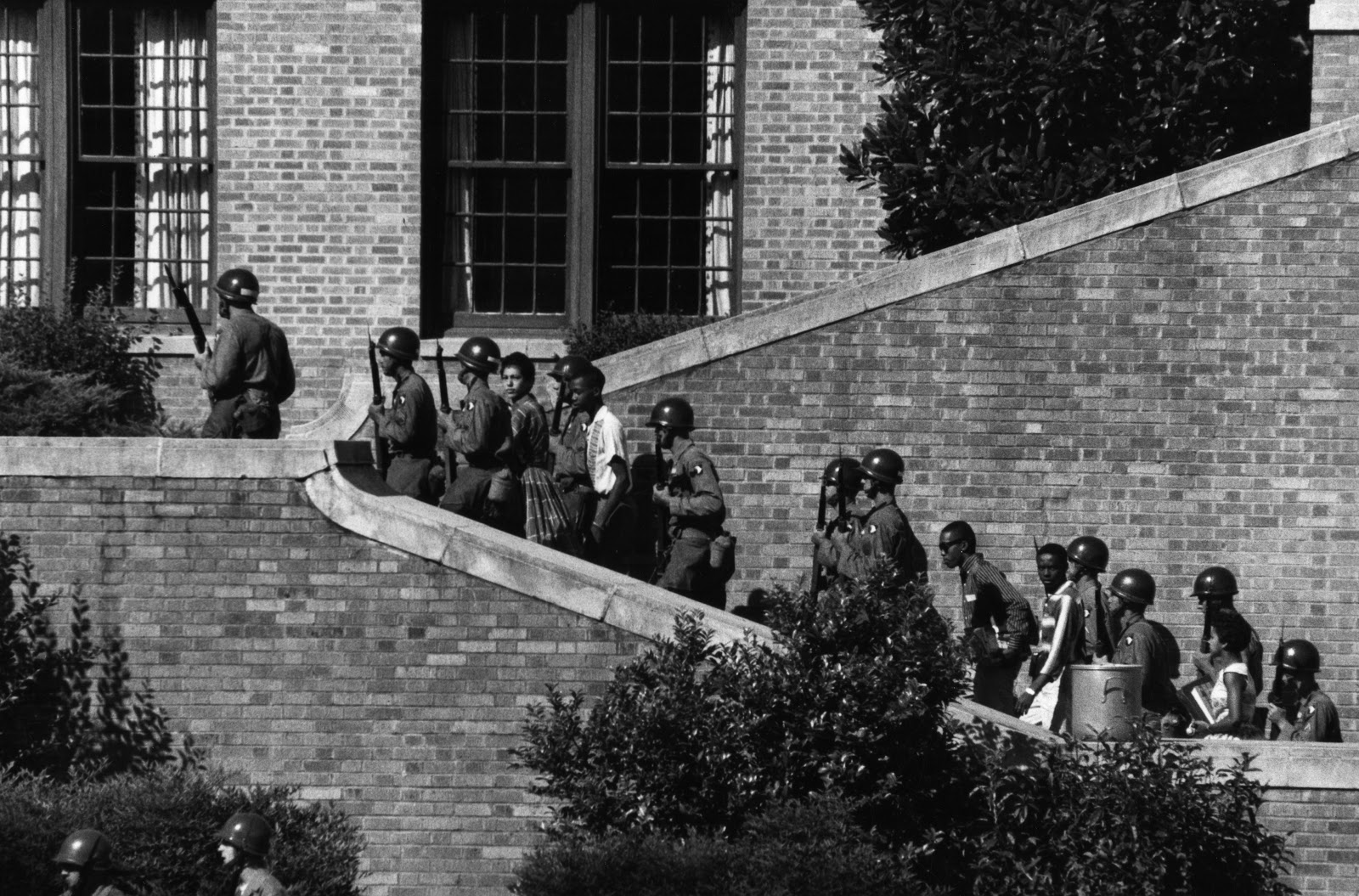

President Eisenhower believed in the cause of Civil Rights but he also believed that morality—equal treatment of both races in this case—could not be legislated. Nonetheless, when the first serious challenge to this ruling arose in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957, Eisenhower, who took seriously his role as one who “executes” the law, federalized the Arkansas National Guard and mobilized the 101st Airborne to ensure integration of the Little Rock High School.

Video (00:05:00): Finish Eisenhower (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=452421)

Governor Orval Faubus had attempted to block a desegregation plan calling for the admission of nine black students to the city’s previously all-white Central High School. After futile efforts at negotiation, the president sent federal troops to Little Rock to enforce the plan. Governor Faubus responded by ordering the Little Rock high schools closed down for the 1958-59 school year. However, a federal court ordered them reopened the following year. They did so in a tense atmosphere with a tiny number of African-American students. Thus, school desegregation proceeded at a slow and uncertain pace throughout much of the South.

Video (00:02:51): Dexter Avenue (https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1XfYYishbP8_wRj6l9I4fTMu2ep5LOUZUwPT5pfVyU-Y/edit?usp=sharing)

Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort the Little RockNine students into the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. By US Army [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Bus Boycott

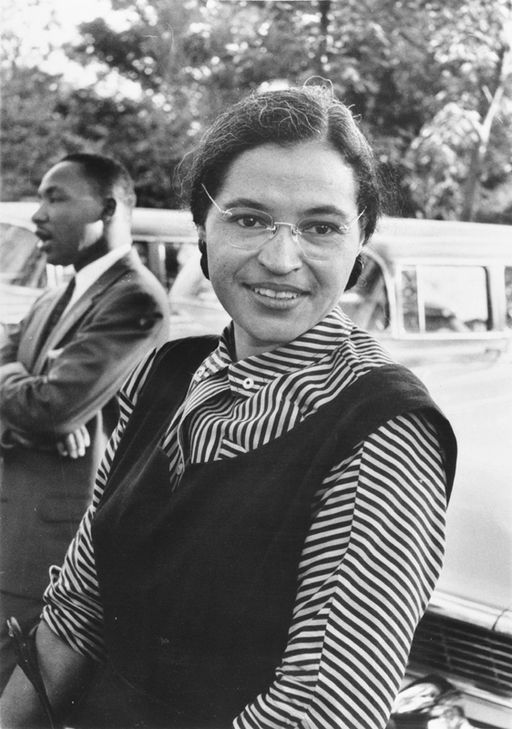

Another milestone in the civil rights movement occurred in 1955, in Montgomery Alabama, when Rosa Parks (who was also secretary of the state chapter of the NAACP) refused to give up her seat to a white man and remove herself to the rear of the bus. African-American leaders, who had been waiting for just such a case, organized a boycott of the bus system. The boycott, made possible by extensive carpooling, was led by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. His persuasive use of non-violent civil disobedience proved to be the perfect blend of W.E.B. Dubois' call for aggressive action and Booker T. Washington's call for peaceful coexistence 60 years earlier. Here was a method that could garner both goodwill and results.

Video (00:02:09) Arrest site (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Lt76Trw3)

Martin Luther King Jr., a young minister of the Baptist church where the African Americans met, became a spokesman for the protest. “There comes a time,” he said, “when people get tired ... of being kicked about by the brutal feet of oppression.” King was arrested, as he would be again and again; a bomb damaged the front of his house. But African Americans in Montgomery sustained the boycott. About a year later, the Supreme Court affirmed that bus segregation, like school segregation, was unconstitutional. The boycott ended. The civil rights movement had won an important victory — and discovered its most powerful, thoughtful, and eloquent leader in Martin Luther King Jr.

New Civil Rights Legislation

African Americans also sought to secure their voting rights. Although the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right to vote, many states had found ways to circumvent the law. The states would impose a poll (“head”) tax or a literacy test — typically much more stringently interpreted for African Americans — to prevent poor African Americans with little education from voting. Eisenhower, working with Senate majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson, lent his support to a congressional effort to guarantee the vote. The Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first such measure in 82 years, marked a step forward, as it authorized federal intervention in cases where African Americans were denied the chance to vote. Yet loopholes remained, and so activists pushed successfully for the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which provided stiffer penalties for interfering with voting, but still stopped short of authorizing federal officials to register African Americans.

Relying on the efforts of African Americans themselves, the Civil Rights movement gained momentum in the postwar years. Working through the Supreme Court and through Congress, civil rights supporters had created the groundwork for a dramatic yet peaceful “revolution” in American race relations in the 1960s.

By 1960, the United States was on the verge of a major social change. American society had always been more open and fluid than that of the nations in most of the rest of the world. Still, it had been dominated primarily by old-stock, white males. During the 1960s, groups that previously had been submerged or subordinate began more forcefully and successfully to assert themselves: African Americans, Native Americans, women, the white ethnic offspring of the “new immigration,” and Latinos. Much of the support they received came from a young population larger than ever, making its way through a college and university system that was expanding at an unprecedented pace. Frequently embracing “countercultural” lifestyles and radical politics, many of the offspring of the World War II generation emerged as advocates of a new America characterized by a cultural and ethnic pluralism that their parents often viewed with unease.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 1960-1980

The struggle of African Americans for equality reached its peak in the mid-1960s. After progressive victories in the 1950s, African Americans became even more committed to nonviolent direct action. Groups like the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), made up of African-American clergy, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee(SNCC), composed of younger activists, sought reform through peaceful confrontation.

Video (00:07:58) Freedom to Sit, Freedom to Ride (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=47589&loid=411512)

In 1960 African-American college students sat down at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in North Carolina and refused to leave. Media attention spawned other sit-ins involving blacks and whites sympathetic to the cause. The next year the Congress On Racial Equality (CORE) engaged in freedom rides to test the Federal Government’s will to enforce desegregation in southern bus systems. Any arrest by southern authorities would be a direct challenge to the Supreme Court’s ruling.

They also organized rallies, the largest of which was the “March on Washington” in 1963. More than 200,000 people gathered in the nation’s capital to demonstrate their commitment to equality for all. The high point of a day of songs and speeches came with the address of Martin Luther King Jr., who had emerged as the preeminent spokesman for civil rights. “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” King proclaimed. Each time he used the refrain “I have a dream,” the crowd roared.

![By Photo by Warren K. Leffler [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3922)

By Photo by Warren K. Leffler [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

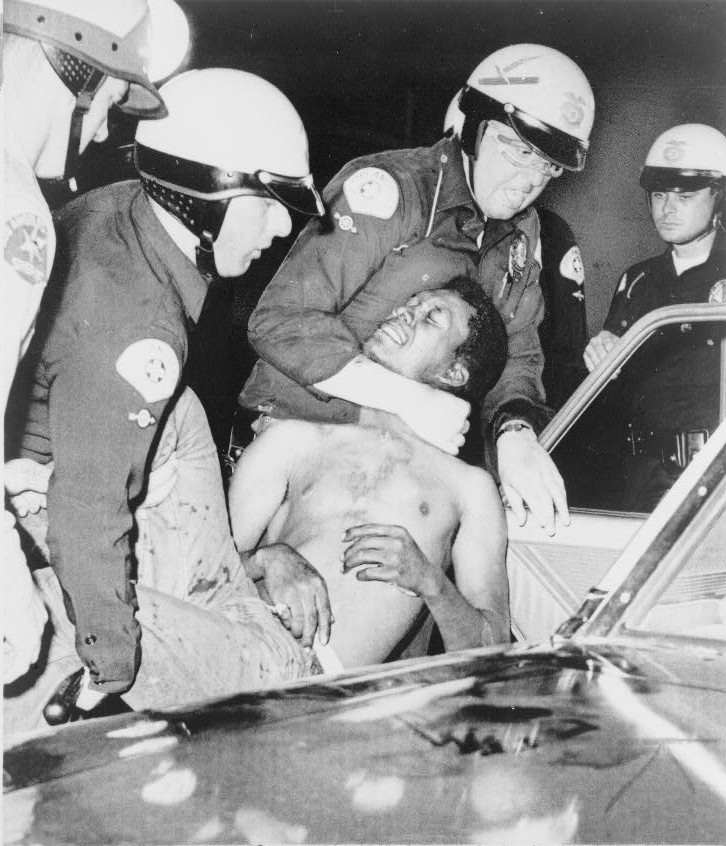

Television and Civil Rights

Television proved a powerful ally as white T.V. audiences around the country watched as peaceful, well-dressed blacks were assaulted by police dogs, batons and fire hoses. Public opinion began to favor the Civil Rights activists.

The level of progress initially achieved did not match the rhetoric of the civil rights movement. President Kennedy was initially reluctant to press white Southerners for support on civil rights because he needed their votes on other issues. Events, driven by African Americans themselves, forced his hand. When James Meredith was denied admission to the University of Mississippi in 1962 because of his race, Kennedy sent federal troops to uphold the law. After protests aimed at the desegregation of Birmingham, Alabama, prompted a violent response by the police, he sent Congress a new civil rights bill mandating the integration of public places. Not even the March on Washington, however, could extricate the measure from a congressional committee, where it was still bottled up when Kennedy was assassinated in 1963.

Video (00:16:21) Kennedy and Civil Rights (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=47589&loid=411512)

Breakthrough

The assassination of John F. Kennedy may rank alongside the assassinations of Julius Caesar, and Franz Ferdinand in terms of influence upon Western Civilization. Kennedy had won the election of 1960 by a hair. Accordingly, his belief in the cause of Civil Rights was held hostage by his clear lack of an electoral mandate for reform and his need for southern support on foreign policy issues, especially his efforts to contain Communism.

Video (00:03:24) Kennedy assassination (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=47589&loid=411512)

After forcing integration at the Universities of Mississippi and Alabama, Kennedy finally put forward a Civil Rights bill which would ban discrimination wherever federal money was involved. The Bill stalled in Congress in 1963 just as Martin Luther King Jr. presided over the “March on Washington” that drew a quarter of a million people hoping to prod the timid Kennedy administration into a more aggressive stance on civil rights. Upon Kennedy's assassination, the new President Lyndon Johnson—the architect of Kennedy's Civil Rights bill—pushed the stalled bill through a sympathetic and grieving Congress. In its final form, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in all public accommodations. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 also empowered the Attorney General of the U.S. to register (and protect) black voters in the South. Nearly half a million blacks registered to vote within a year. By 1968 a million African Americans were registered in the deep South. Nationwide, the number of African- American elected officials increased substantially. In 1968, the Congress passed legislation banning discrimination in housing.

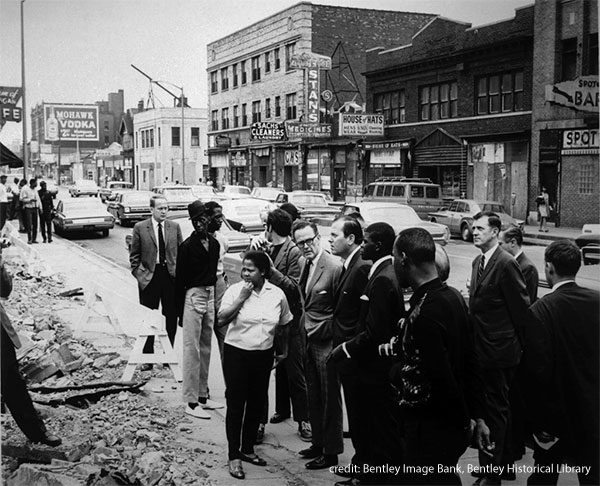

Violence

Just as King's strongly Christian-influenced, non-violent approach began to pay dividends, Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael began to preach the failure of non-violence. Though the law of the land had changed, actual circumstances moved much slower. It would take time to enforce the law and men like X and Carmichael were, understandably, out of patience. They became part of the “Black Muslim” movement, advocated “Black Power” and adhered to a doctrine of separation from whites just as commingling equally with whites had become a real possibility. In a grand irony, the Congress On Racial Equality and the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) respectively, threw out their white members and advocated violence against whites.

This time television worked against the Civil Rights movement as white Americans watched the results of riots and looting in Los Angeles, Detroit and other metropolitan areas. The assassinations of X, King and yet another Kennedy (Robert) did little to improve and much to deflate the Civil Rights movement. These did, however, signal a new era in the United States—an era of violence, social change and youth and minority empowerment.

To many, these two assassinations marked the end of an era of innocence and idealism. The growing militancy on the left, coupled with an inevitable conservative backlash, opened a rift in the nation’s psyche that has yet to heal.

By then, however, a civil rights movement supported by court decisions, congressional enactments, and federal administrative regulations was irreversibly woven into the fabric of American life. The major issues were about implementation of equality and access, not about the legality of segregation or disenfranchisement. The arguments of the 1970s and thereafter were over matters such as busing children out of their neighborhoods to achieve racial balance in metropolitan schools or about the use of “affirmative action.” These policies and programs were viewed by some as active measures to ensure equal opportunity, as in education and employment, and by others as reverse discrimination.

The courts worked their way through these problems with decisions that were often inconsistent. In the meantime, the steady march of African Americans into the ranks of the middle class and once largely white suburbs quietly reflected a profound demographic change.

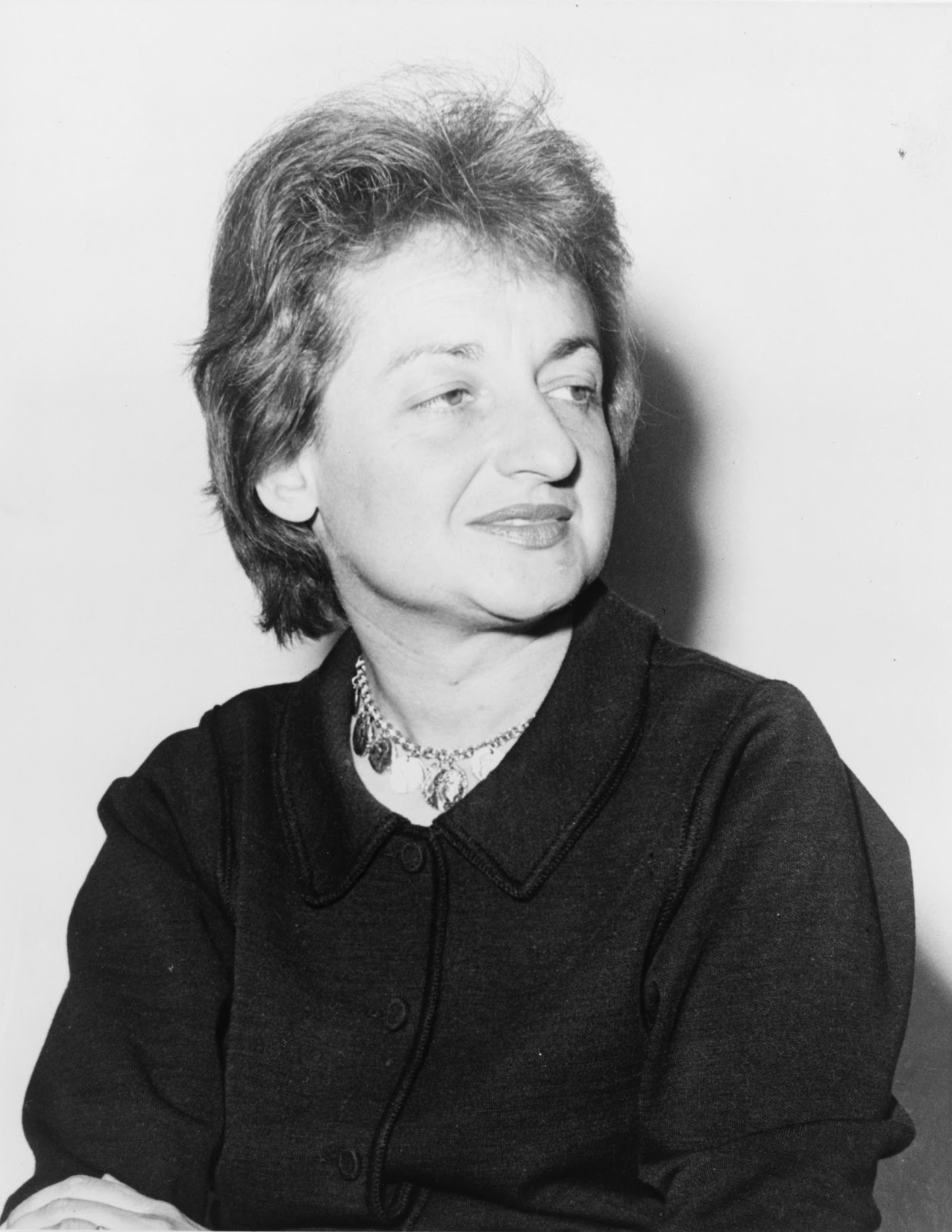

THE WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

During the 1950s and 1960s, increasing numbers of married women entered the labor force, but in 1963 the average working woman earned only 63 percent of what a man made. That year Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, an explosive critique of middle class living patterns that articulated a pervasive sense of discontent that Friedan contended was felt by many women. Arguing that women often had no outlets for expression other than “finding a husband and bearing children,” Friedan encouraged her readers to seek new roles and responsibilities and to find their own personal and professional identities, rather than have them defined by a male-dominated society.

The women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s drew inspiration from the Civil Rights movement. It was made up mainly of members of the middle class, and thus partook of the spirit of rebellion that affected large segments of middle-class youth in the 1960s. Ironically, within the Civil Rights movement women found themselves most oppressed as they were relegated to cooking, cleaning and serving. “The only position for women in SNCC” — said Stokely Carmichael— “is prone.”

Reform legislation also prompted change. During debate on the 1964 Civil Rights bill, opponents hoped to defeat the entire measure by proposing an amendment to outlaw discrimination on the basis of gender as well as race. First the amendment, then the bill itself, passed, giving women a valuable legal tool.

NOW

In 1966, 28 professional women, including Friedan, established the National Organization for Women (NOW) “to take action to bring American women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now.” While NOW and similar feminist organizations boast of substantial memberships today, arguably they attained their greatest influence in the early 1970s, a time that also saw the journalist Gloria Steinem and several other women found Ms. magazine. They also spurred the formation of counter-feminist groups, often led by women, including most prominently the political activist Phyllis Schlafly. These groups typically argued for more “traditional” gender roles and opposed the proposed “Equal Rights” constitutional amendment.

ERA

Passed by Congress in 1972, that amendment declared in part, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Over the next several years, 35 of the necessary 38 states ratified it. The courts also moved to expand women’s rights. In 1973 the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade established women’s right to obtain an abortion during the early months of pregnancy. Feminists were divided over the Roe v. Wade decision legalizing abortion. Some viewed it as a victory for all women, others as a defeat for unborn women.

In the mid- to late-1970s, however, the women’s movement seemed to stagnate. It failed to broaden its appeal beyond the middle class. Divisions arose between moderate and radical feminists. Conservative opponents mounted a campaign against the Equal Rights Amendment, and it died in 1982 without gaining the approval of the 38 states needed for ratification.

THE LATINO MOVEMENT

In post-World War II America, Americans of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent had faced discrimination. New immigrants, coming from Cuba, Mexico, and Central America — often unskilled and unable to speak English — suffered from discrimination as well. Some Hispanics worked as farm laborers and at times were cruelly exploited while harvesting crops; others gravitated to the cities, where, like earlier immigrant groups, they encountered difficulties in their quest for a better life.

Video (00:03:34) Migrant Workers (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Cd3t6Q4G)

Chicanos, or Mexican-Americans, mobilized in organizations like the radical Asociación Nacional Mexico-Americana, yet did not become confrontational until the 1960s. Hoping that Lyndon Johnson’s poverty program would expand opportunities for them, they found that bureaucrats failed to respond to less vocal groups. The example of black activism in particular taught Hispanics the importance of pressure politics in a pluralistic society.

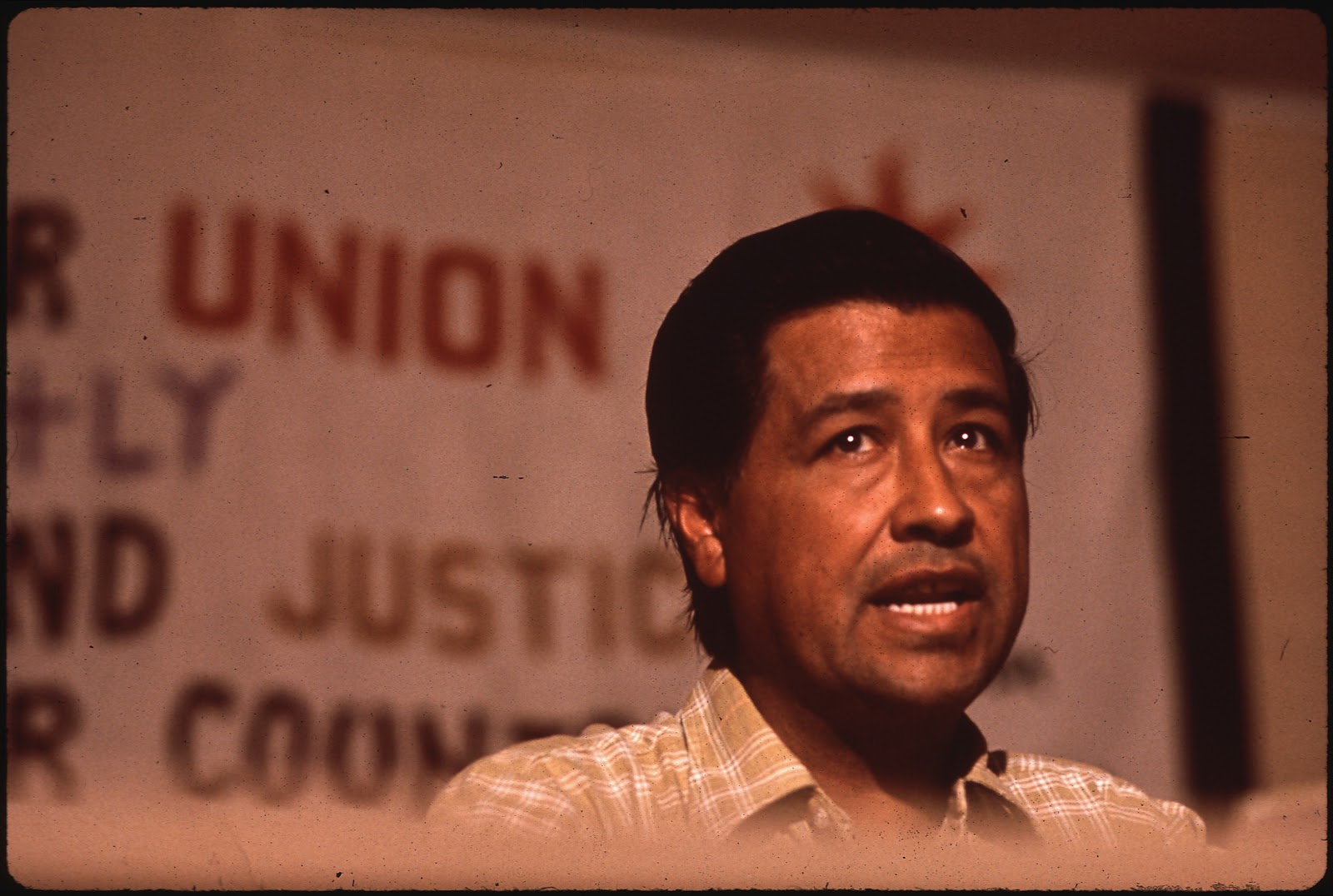

Cesar Chavez

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 had excluded agricultural workers from its guarantee of the right to organize and bargain collectively. But César Chávez, founder of the overwhelmingly Hispanic United Farm Workers, demonstrated that direct action could achieve employer recognition for his union. California grape growers agreed to bargain with the union after Chávez led a nationwide consumer boycott. Similar boycotts of lettuce and other products were also successful. Though farm interests continued to try to obstruct Chávez’s organization, the legal foundation had been laid for representation to secure higher wages and improved working conditions.

Hispanics became politically active as well. In 1961 Henry B. González won election to Congress from Texas. Three years later Eligio (“Kika”) de la Garza, another Texan, followed him, and Joseph Montoya of New Mexico went to the Senate. Both González and de la Garza later rose to positions of power as committee chairmen in the House. In the 1970s and 1980s, the pace of Hispanic political involvement increased. Several prominent Hispanics have served in the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush cabinets.

THE NATIVE-AMERICAN MOVEMENT

In the 1950s, Native Americans struggled with the government’s policy of moving them off reservations and into cities where they might assimilate into mainstream America. Many of the uprooted often had difficulties adjusting to urban life. In 1961, when the policy was discontinued, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights noted that, for Native Americans, “poverty and deprivation are common.”

AIM

In the 1960s and 1970s, watching both the development of Third World nationalism and the progress of the civil rights movement, Native Americans became more aggressive in pressing for their own rights. A new generation of leaders went to court to protect what was left of tribal lands or to recover those which had been taken, often illegally, in previous times. In state after state, they challenged treaty violations, and in 1967 won the first of many victories guaranteeing long-abused land and water rights. The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, helped channel government funds to Native-American-controlled organizations and assisted Native Americans in the cities.

Alcatraz and Wounded Knee

Confrontations became more common. In 1969 a landing party of 78 Native Americans seized Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay and held it until federal officials removed them in 1971. In 1973 AIM took over the South Dakota village of Wounded Knee, where soldiers in the late 19th century had massacred a Sioux encampment. Militants hoped to dramatize the poverty and alcoholism in the reservation surrounding the town. Hostages they had taken would not be released until the government agreed to revisit treaty rights for the Oglala Sioux. The episode ended after one Native American was killed and another wounded, with a government agreement to re-examine treaty rights.

Still, Native-American activism brought results. Other Americans became more aware of Native-American issues. Government officials responded with measures including the Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the 1996 Native-American Housing and Self-Determination Act. The Senate’s first Native-American member, Ben Nighthorse Campbell of Colorado, was elected in 1992.

THE COUNTERCULTURE

The Counterculture of the 1960s and early 1970s can be traced back at least as far as the “beatniks” of the 1950s. The “beats,” like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, rejected the conformist culture of the 1950s in favor of travel, unrestrained sexual expression, alcohol, and drugs.

![Contestants for the 'Miss Beatnik' competition. By Photographer for Los Angeles Times [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3923)

Contestants for the 'Miss Beatnik' competition. By Photographer for Los Angeles Times [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Contestants for the 'Miss Beatnik' competition. By Photographer for Los Angeles Times [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

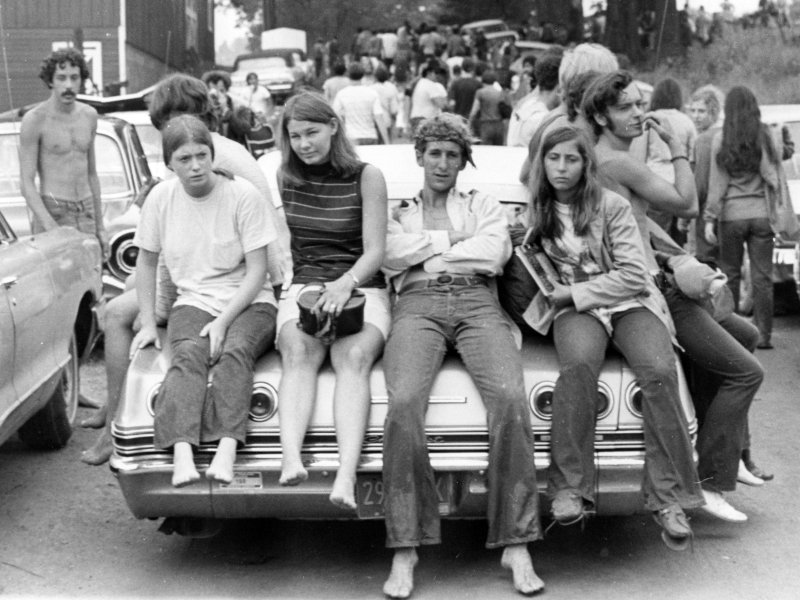

The visible signs of the counterculture spread through parts of American society in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Hair grew longer and beards became common. Blue jeans and tee shirts took the place of slacks, jackets, and ties. The use of illegal drugs increased. Rock and roll grew, proliferated, and transformed into many musical variations. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other British groups took the country by storm. “Hard rock” grew popular, and songs with a political or social commentary, such as those by singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, became common. The youth counterculture reached its apogee in August 1969 at Woodstock, a three-day music festival in rural New York State attended by almost half-a-million persons. The festival, mythologized in films and record albums, gave its name to the era, the Woodstock Generation.

The New Left

A parallel manifestation of the new sensibility of the young was the rise of the New Left, a group of young, college-age radicals. The New Leftists, who had close counterparts in Western Europe, were in many instances the children of the older generation of radicals. Nonetheless, they rejected old-style Marxist rhetoric. Instead, they depicted university students as themselves an oppressed class that possessed special insights into the struggle of other oppressed groups in American society.

The New Left of the early 1960s rejected both political parties as having an interest in the “establishment” and its continuation. In a wholesale rejection of that establishment, Tom Hayden and Al Haber founded the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) at the University of Michigan in 1960. To students like Haber and Hayden, the university system supported the “establishment” through military and corporate support of research. The university system was guilty by association in their eyes. Accordingly they saw it as the perfect place to begin.

The Port Huron Statement

In Port Huron, Michigan in 1962, Hayden wrote the “Port Huron Statement” in which he called on students to overthrow the “establishment” which was represented, in his mind, by racism, Cold War, poverty and corporate wealth. At Berkley in 1964, the first student sit-in occurred when a CORE member was expelled for recruiting to his organization. Berkley students responded by “sitting-in” the administration building and shutting down the campus and demanding “Free Speech.” By 1967, campus sit-ins had become widespread, and students were openly challenging the war in Vietnam, as well as social mores pertaining to sex, language, attire and drug use. Such behavior attracted non-college-going middle and upper class children of about the same age who styled themselves “hippies.”

Hippies

The hippies were not nearly as politically motivated as the SDS; neither were they as benign a community as they styled themselves. They were content to rebel against the affluent and middle classes, as well as the “establishment” which had spawned them. They did so through “tuning in, turning on and dropping out.” Paradoxically, the “establishment” had made it possible for them to engage in their rebellion without starving due to the raft of social legislation LBJ had pushed through the Congress earlier in the decade. Hippies were decidedly against the war but tended not to follow any organized plan to oppose it.

Questioning what they perceived as the materialistic values of their parents, hippies sought enlightenment through Eastern religions, long hair, drugs, folk music, unrestrained sex and communal living. Not surprisingly, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) spiked during the 1960s and 1970s as did organized crime as a new wave of drug addiction fueled a new generation of crime lords. The inner cities became dominated by this new pandemic of drug use and drug pushing.

New Leftists participated in the Civil Rights movement and the struggle against poverty. Their greatest success — and the one instance in which they developed a mass following — was in opposing the Vietnam War, an issue of emotional interest to their draft-age contemporaries. By the late 1970s, the student New Left had disappeared, but many of its activists made their way into mainstream politics.

Justification

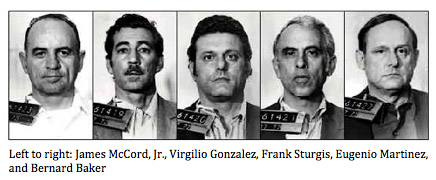

That college students and hippies had something to rebel against (the “establishment), seemed to them justified by the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate incident. The Pentagon Papers, stolen by Department of Defense employee Daniel Ellsberg and leaked to the Press in 1970, revealed a pattern of deceit in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations regarding the conduct and results of the Vietnam conflict.

The Watergate burglary in 1972, in which President Nixon’s Committee to Reelect the President (CREEP) was implicated, ruined Nixon’s presidency and forced his resignation in August of 1974.

Implications

The Counter-Culture did not come and go as had social phenomena like the roaring twenties. Indeed, the Counterculture was quickly assimilated by corporate America as evidenced by advertising in the 1970s. One could pick up most forms of commercial print by 1975 and see advertisements which pictured young people sporting headbands, long hair, and flower-print shirts. The popular musicians of the Counterculture became fantastically rich and led extravagant lifestyles which neither the culture at large, nor the Counterculture could emulate or easily relate to; in fact, it was partly such extravagance in the culture which had been the source of the recent rebellion.

As a legacy of this era, American Culture has very much reaped what it has sown—a much-enlarged illicit drug trade, continued inner-city decay, more open attitudes toward sex, epidemic STD’s, greater environmental awareness and an increasing adoration of youth at the expense of attitudes toward the elderly and being old.

ENVIRONMENTALISM

The energy and sensibility that fueled the Civil Rights movement, the counterculture, and the New Left also stimulated an environmental movement in the mid-1960s. Many were aroused by the publication in 1962 of Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring, which alleged that chemical pesticides, particularly DDT, caused cancer, among other ills. Public concern about the environment continued to increase throughout the 1960s as many became aware of other pollutants surrounding them — automobile emissions, industrial wastes, oil spills — that threatened their health and the beauty of their surroundings. On April 22, 1970, schools and communities across the United States celebrated Earth Day for the first time. “Teach-ins” educated Americans about the dangers of environmental pollution.

The Cuyahoga River on fire in 1948. Image courtesy of Cleveland State Library Special Collections

The Cuyahoga River on fire in 1948. Image courtesy of Cleveland State Library Special Collections

Few denied that pollution was a problem, but the proposed solutions involved expense and inconvenience. Many believed these would reduce the economic growth upon which many Americans’ standard of living depended. Nevertheless, in 1970, Congress amended the Clean Air Act of 1967 to develop uniform national air-quality standards. It also passed the Water Quality Improvement Act, which assigned to the polluter the responsibility of cleaning up off-shore oil spills. Also, in 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was created as an independent federal agency to spearhead the effort to bring abuses under control. During the next three decades, the EPA, bolstered by legislation that increased its authority, became one of the most active agencies in the government, issuing strong regulations covering air and water quality.

Then & Now, Cuyahoga River, Ohio. Clockwise from left: "City Pump Station Discharges Sewage into the Cuyahoga River," July, 1973 photo by Frank J. Aleksandrowicz for Documerica; Cuyahoga River Today. September, 2012 by Pete Cassell for State of the Environment; One of the Cuyahoga River fires, this event in 1952. (Photo by James Thomas). Images courtesy of Cleveland Press Collection, Cleveland State University Library.

Photoset by US EPA [Public domain], via Flickr Commons

KENNEDY AND THE RESURGENCE OF BIG GOVERNMENT LIBERALISM

By 1960 government had become an increasingly powerful force in people’s lives. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, new executive agencies were created to deal with many aspects of American life. During World War II, the number of civilians employed by the federal government rose from one million to 3.8 million, then stabilized at 2.5 million in the 1950s. Federal expenditures, which had stood at $3.1 billion in 1929, increased to $75 billion in 1953 and passed $150 billion in the 1960s.

Opposing Visions

Most Americans accepted government’s expanded role, even as they disagreed about how far that expansion should continue. Democrats generally wanted the government to ensure growth and stability. They wanted to extend federal benefits for education, health, and welfare. Many Republicans accepted a level of government responsibility, but hoped to cap spending and restore a larger measure of individual initiative. The presidential election of 1960 revealed a nation almost evenly divided between these visions.

John F. Kennedy, the Democratic victor by a narrow margin, was at 43 the youngest man ever to win the presidency. On television, in a series of debates with opponent Richard Nixon, he appeared able, articulate, and energetic. In the campaign, he spoke of moving aggressively into the new decade, for “the New Frontier is here whether we seek it or not.” In his inaugural address, he concluded with an eloquent plea: “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” Throughout his brief presidency, Kennedy’s special combination of grace, wit, and style — far more than his specific legislative agenda — sustained his popularity and influenced generations of politicians to come.

Kennedy wanted to exert strong leadership to extend economic benefits to all citizens, but a razor-thin margin of victory limited his mandate. Even though the Democratic Party controlled both houses of Congress, conservative Southern Democrats often sided with the Republicans on issues involving the scope of governmental intervention in the economy. They resisted plans to increase federal aid to education, provide health insurance for the elderly, and create a new Department of Urban Affairs. And so, despite his lofty rhetoric, Kennedy’s policies were often limited and restrained.

One priority was to end the recession, in progress when Kennedy took office, and restore economic growth. But Kennedy lost the confidence of business leaders in 1962, when he succeeded in rolling back what the administration regarded as an excessive price increase in the steel industry. Though the president achieved his immediate goal, he alienated an important source of support. Persuaded by his economic advisers that a large tax cut would stimulate the economy, Kennedy backed a bill providing for one. Conservative opposition in Congress, however, appeared to destroy any hopes of passing a bill most congressmen thought would widen the budget deficit.

The overall legislative record of the Kennedy administration was meager. The president made some gestures toward civil rights leaders but did not embrace the goals of the civil rights movement until demonstrations led by Martin Luther King Jr. forced his hand in 1963. Like Truman before him, he could not secure congressional passage of federal aid to public education or for a medical care program limited to the elderly. He gained only a modest increase in the minimum wage. Still, he did secure funding for a space program, and established the Peace Corps to send men and women overseas to assist developing countries in meeting their own needs.

KENNEDY AND THE COLD WAR

Video (00:05:29) The Presidents Kennedy (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=411631)

A war veteran and cold-warrior, President John F. Kennedy faced severe tests of Cold War tension in Cuba and Berlin, announced the “Space Race,” and made equivocal attempts at civil rights reform. Kennedy won the election of 1960 against Republican, Richard Nixon, in an extremely close race, which may very well have been determined by his good looks (compared to Nixon’s stiffness and five-o-clock shadow) during the first-ever televised presidential debates.

As an ardent anti-communist, Kennedy was determined to keep the United States ahead of the Soviet Union and presided over a missile build up early in his administration. Developments in Cuba and Berlin only heightened tensions. President Kennedy came into office pledging to carry on the Cold War vigorously, but he also hoped for accommodation and was reluctant to commit American power. During his first year-and-a-half in office, he rejected American intervention after the CIA-guided Cuban exile invasion at the Bay of Pigs failed, effectively ceded the landlocked Southeast Asian nation of Laos to Communist control, and acquiesced in the building of the Berlin Wall.

Bay of Pigs

In 1959, an oppressive and corrupt Cuban government was overthrown by Fidel Castro and his followers. The next year, Castro announced the confiscation of $1 billion of U.S. property in Cuba and his support of Marxism/Leninism. This first appearance of Communism in the Western Hemisphere alarmed the new American president. Kennedy learned of a C.I.A. plan, first authorized by Eisenhower, in which exiled Cubans would invade the Bay of Pigs and start a general uprising against Castro. He gave the go ahead and the plan was launched in April of 1961.

The invasion force of less than 1,500 was quickly defeated; the Administration looked foolish; and Latin-American countries lost a measure of trust in the United States which had come off as a hemispheric meddler.

Berlin Wall

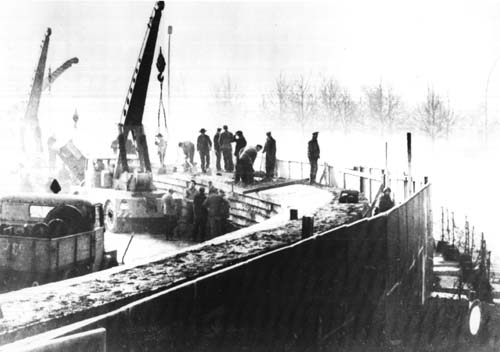

An eastern-bloc “brain drain” in Berlin precipitated another crisis for the Kennedy administration when the Soviets built a wall separating East Berlin from West Berlin. Scientists and intellectuals were escaping the Soviet-bloc to the tune of more than 500 per day by using the subway from East to West Berlin. The Soviets sought to establish a unified Berlin in hopes of dominating it and plugging this substantial leak of brain power. Kennedy resisted, called for additional money for the armed forces, and for a series of civil defense air-raid shelters—a clear indication that the Americans were prepared to go to war over the issue—and the Soviets responded by beginning construction on a wall to divide the city in the late Summer of 1961. Kennedy’s decisions reinforced impressions of weakness that Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had formed in their only personal meeting, a summit meeting at Vienna in June 1961. It was against this backdrop that Kennedy faced the most serious event of the Cold War, the Cuban missile crisis.

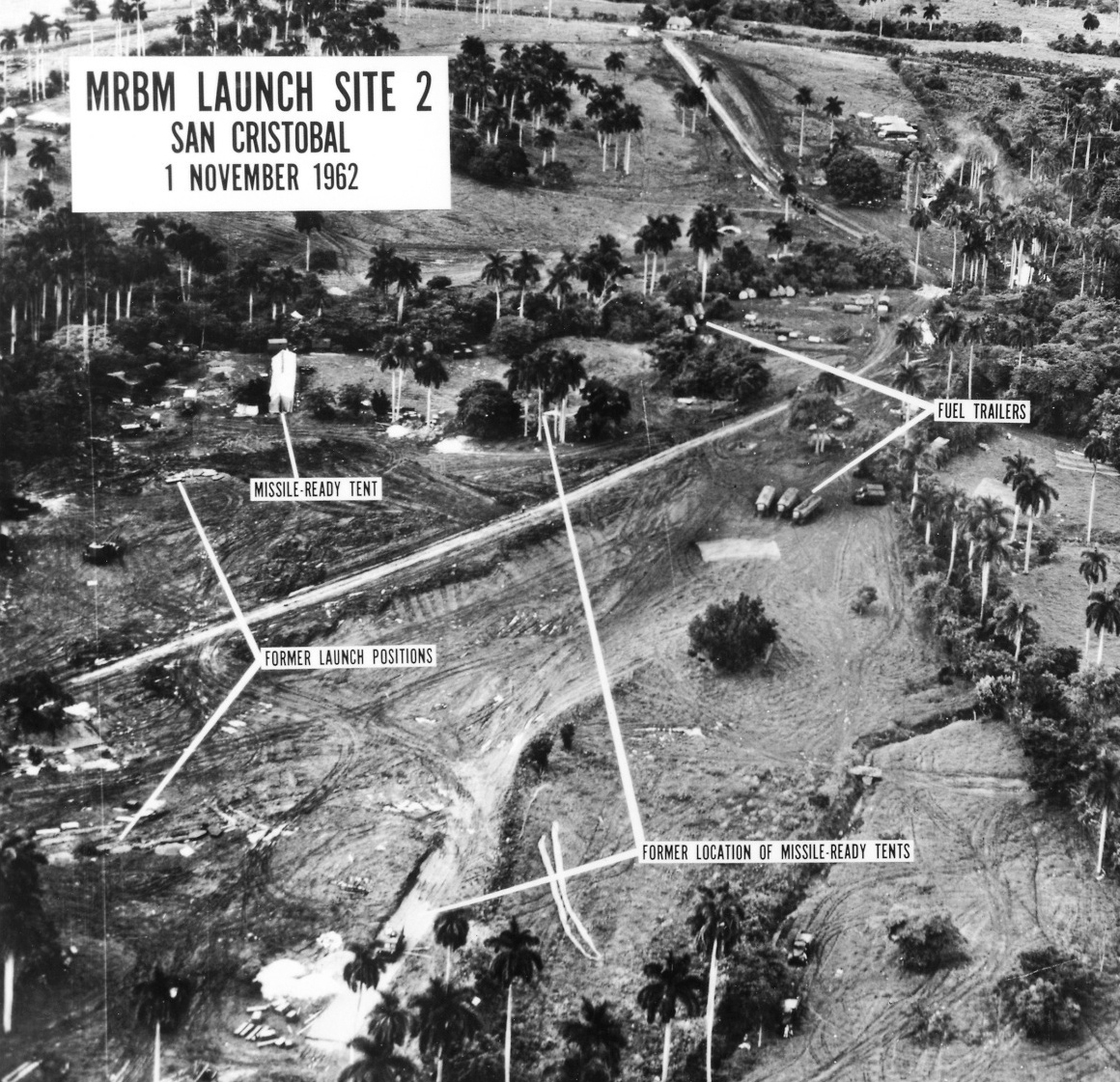

Cuban Missile Crisis

In the fall of 1962, the administration learned that the Soviet Union was secretly installing offensive nuclear missiles in Cuba. After considering different options, Kennedy decided on a quarantine to prevent Soviet ships from bringing additional supplies to Cuba. He demanded publicly that the Soviets remove the weapons and warned that an attack from that island would bring retaliation against the USSR. After several days of tension, during which the world was closer than ever before to nuclear war, the Soviets agreed to remove the missiles. Critics charged that Kennedy had risked nuclear disaster when quiet diplomacy might have been effective. But most Americans and much of the non-Communist world applauded his decisiveness. The missile crisis made him for the first time the acknowledged leader of the democratic West.

In retrospect, the Cuban missile crisis marked a turning point in U.S.-Soviet relations. Both sides saw the need to defuse tensions that could lead to direct military conflict. The following year, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain signed a landmark Limited Test Ban Treaty prohibiting nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere.

Uncertainty in Indochina

Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia), a French possession before World War II, was yet another Cold War battlefield. The French effort to reassert colonial control there was opposed by Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese Communist, whose Viet Minh movement engaged in a guerrilla war with the French army.

Both Truman and Eisenhower, eager to maintain French support for the policy of containment in Europe, provided France with economic aid that freed resources for the struggle in Vietnam. But the French suffered a decisive defeat in Dien Bien Phu in May 1954. At an international conference in Geneva, Laos and Cambodia were given their independence. Vietnam was divided, with Ho in power in the North and Ngo Dinh Diem, a Roman Catholic anti-Communist in a largely Buddhist population, heading the government in the South. Elections were to be held two years later to unify the country. Persuaded that the fall of Vietnam could lead to the fall of Burma, Thailand, and Indonesia, Eisenhower backed Diem’s refusal to hold elections in 1956 and effectively established South Vietnam as an American client state.

Kennedy increased assistance, and sent small numbers of military advisers, but a new guerrilla struggle between North and South continued. Diem’s unpopularity grew and the military situation worsened. In late 1963, Kennedy secretly assented to a coup d’etat. To the president’s surprise, Diem and his powerful brother-in-law, Ngo Dien Nu, were killed. It was at this uncertain juncture that Kennedy’s presidency ended three weeks later.

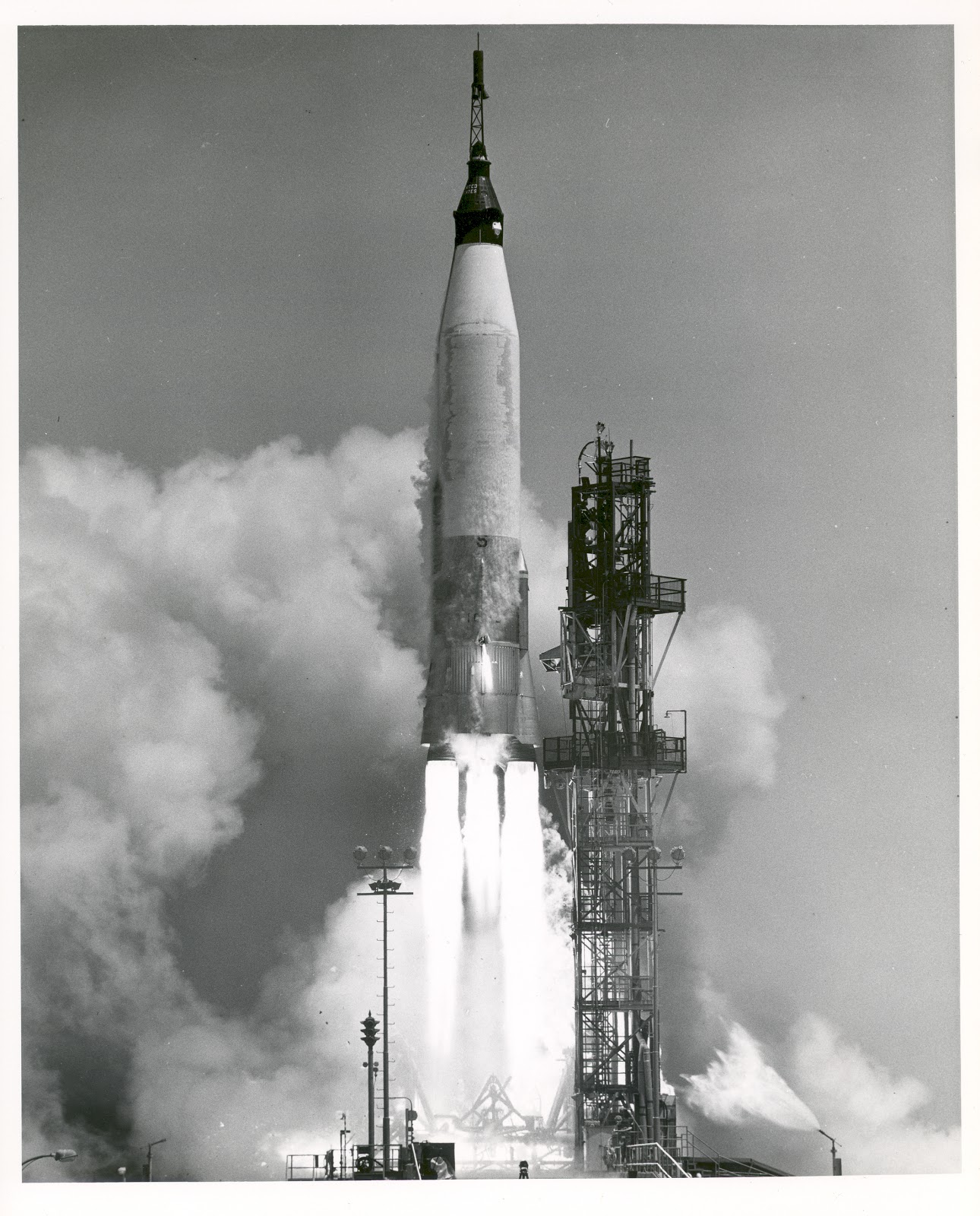

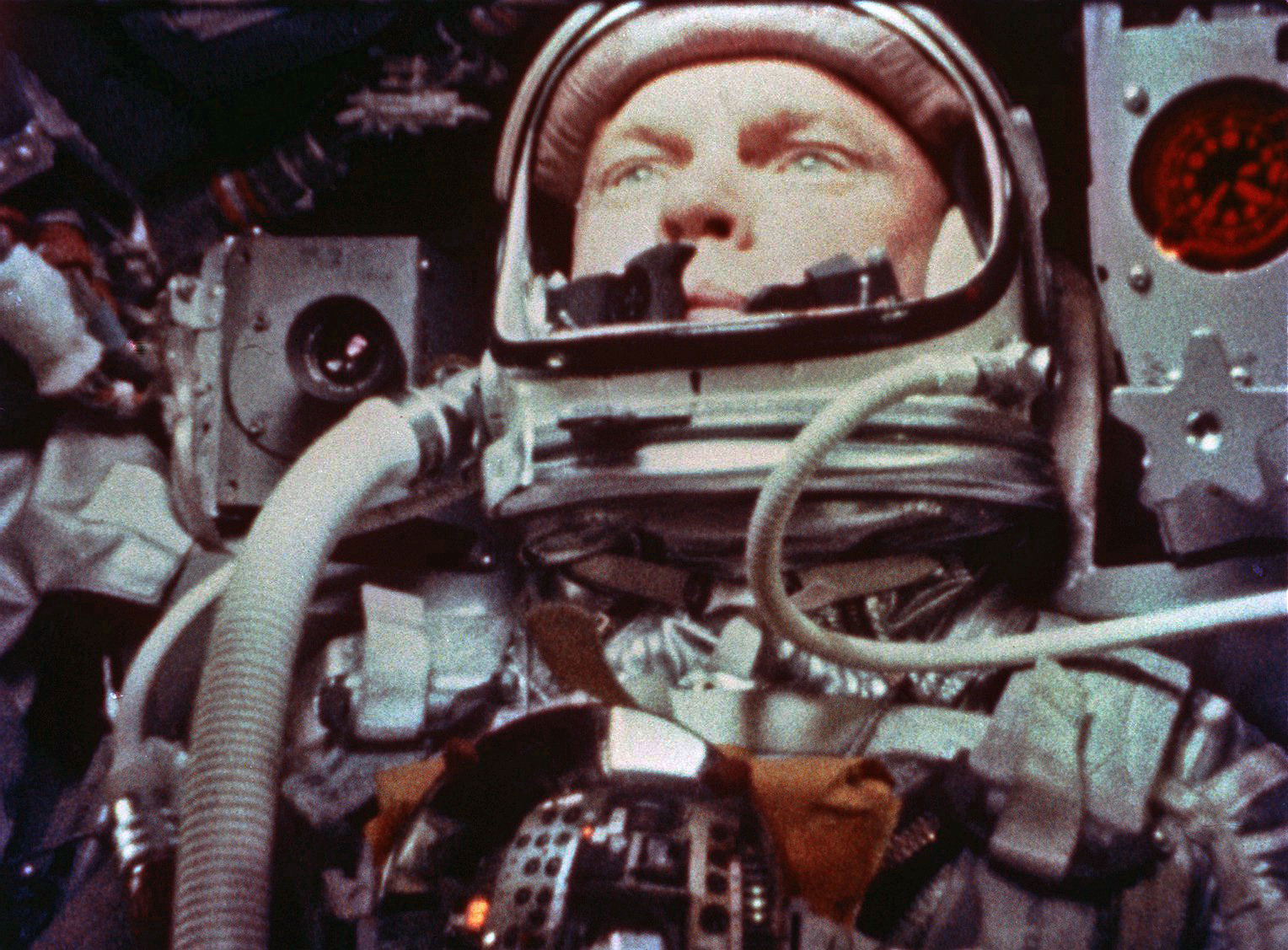

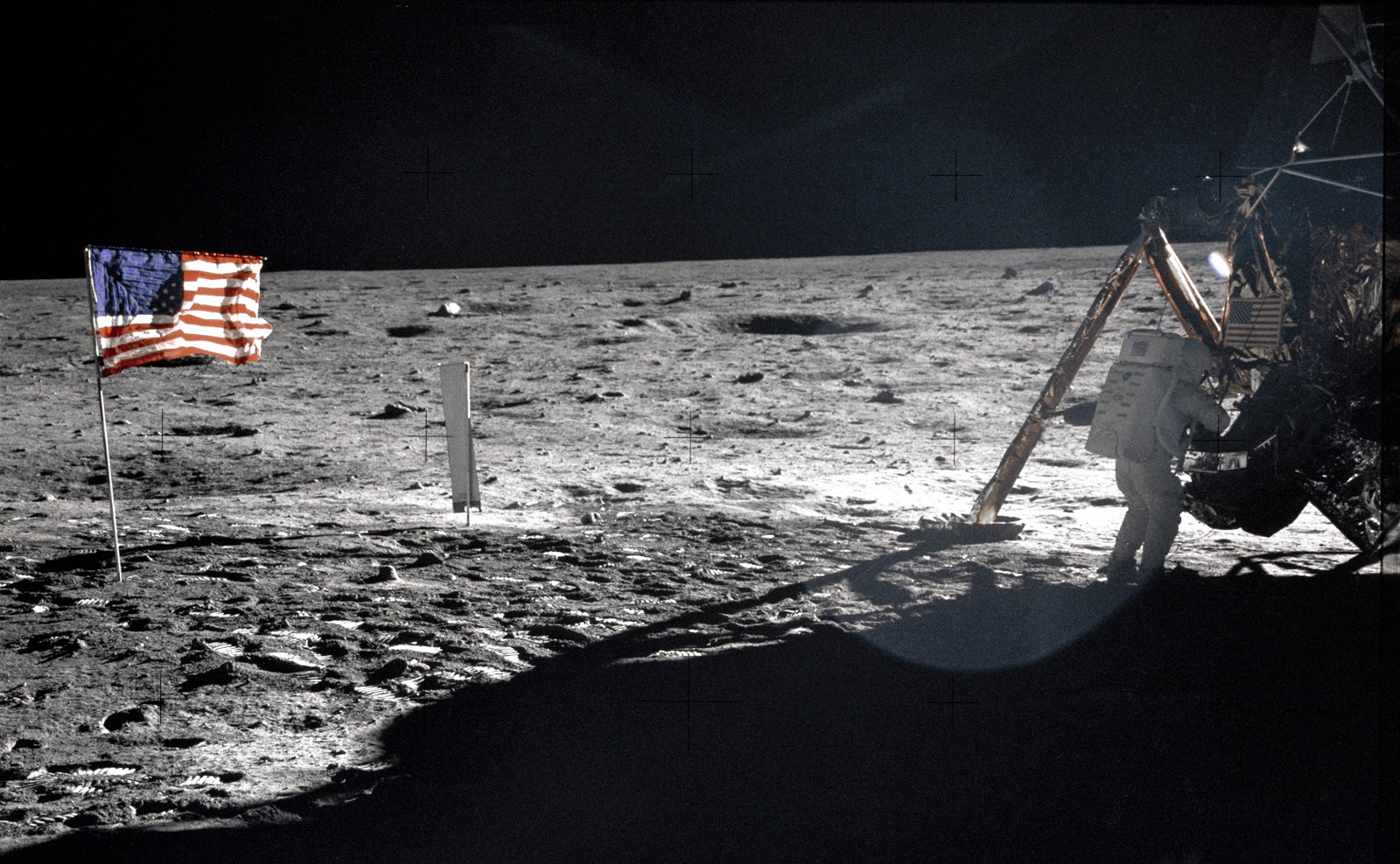

THE SPACE PROGRAM

During Eisenhower’s second term, outer space had become an arena for U.S.-Soviet competition. In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik — an artificial satellite — thereby demonstrating it could build more powerful rockets than the United States. The United States launched its first satellite, Explorer I, in 1958. But three months after Kennedy became president, the USSR put the first man in orbit. Kennedy responded by committing the United States to land a man on the moon and bring him back “before this decade is out.” With Project Mercury in 1962, John Glenn became the first U.S. astronaut to orbit the Earth.

After Kennedy’s death, President Lyndon Johnson enthusiastically supported the space program. In the mid-1960s, U.S. scientists developed the two-person Gemini spacecraft. Gemini achieved several firsts, including an eight-day mission in August 1965 — the longest space flight at that time — and in November 1966, the first automatically controlled reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere. Gemini also accomplished the first manned linkup of two spacecraft in flight as well as the first U.S. walks in space.

The three-person Apollo spacecraft achieved Kennedy’s goal and demonstrated to the world that the United States had surpassed Soviet capabilities in space. On July 20, 1969, with hundreds of millions of television viewers watching around the world, Neil Armstrong became the first human to walk on the surface of the moon.

Other Apollo flights followed, but many Americans began to question the value of manned space flight. In the early 1970s, as other priorities became more pressing, the United States scaled down the space program. Some Apollo missions were scrapped; only one of two proposed Skylab space stations was built.

DEATH OF A PRESIDENT

John Kennedy had gained world prestige by his management of the Cuban missile crisis and had won great popularity at home. Many believed he would win re-election easily in 1964. But on November 22, 1963, he was assassinated while riding in an open car during a visit to Dallas, Texas. His death, amplified by television coverage, was a traumatic event, just as Roosevelt’s had been 18 years earlier.

In retrospect, it is clear that Kennedy’s reputation stems more from his style and eloquently stated ideals than from the implementation of his policies. He had laid out an impressive agenda but at his death much remained blocked in Congress. It was largely because of the political skill and legislative victories of his successor that Kennedy would be seen as a force for progressive change.

Video (00:02:49) Kennedy (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=411642)

Residuals

In addition to its effect on Civil Rights, Kennedy’s assassination also gave greater momentum to his call to send a man to the moon. With renewed vigor, the United States invested in the space program and reaped the benefits and consequences of advanced space-age technology. This technology was applied to missile technology and consumer goods with a net effect of increasing Soviet fears and a Soviet rededication to not falling behind the Americans. The economic and social cost of keeping up with the Americans would (in the future) bankrupt and collapse the Soviet system. A burgeoning American consumer goods market would make possible (in the future) a home-computing market which would (in the future) make possible the internet. In part, these dramatic changes are traceable to a November day in Dallas, in 1963.

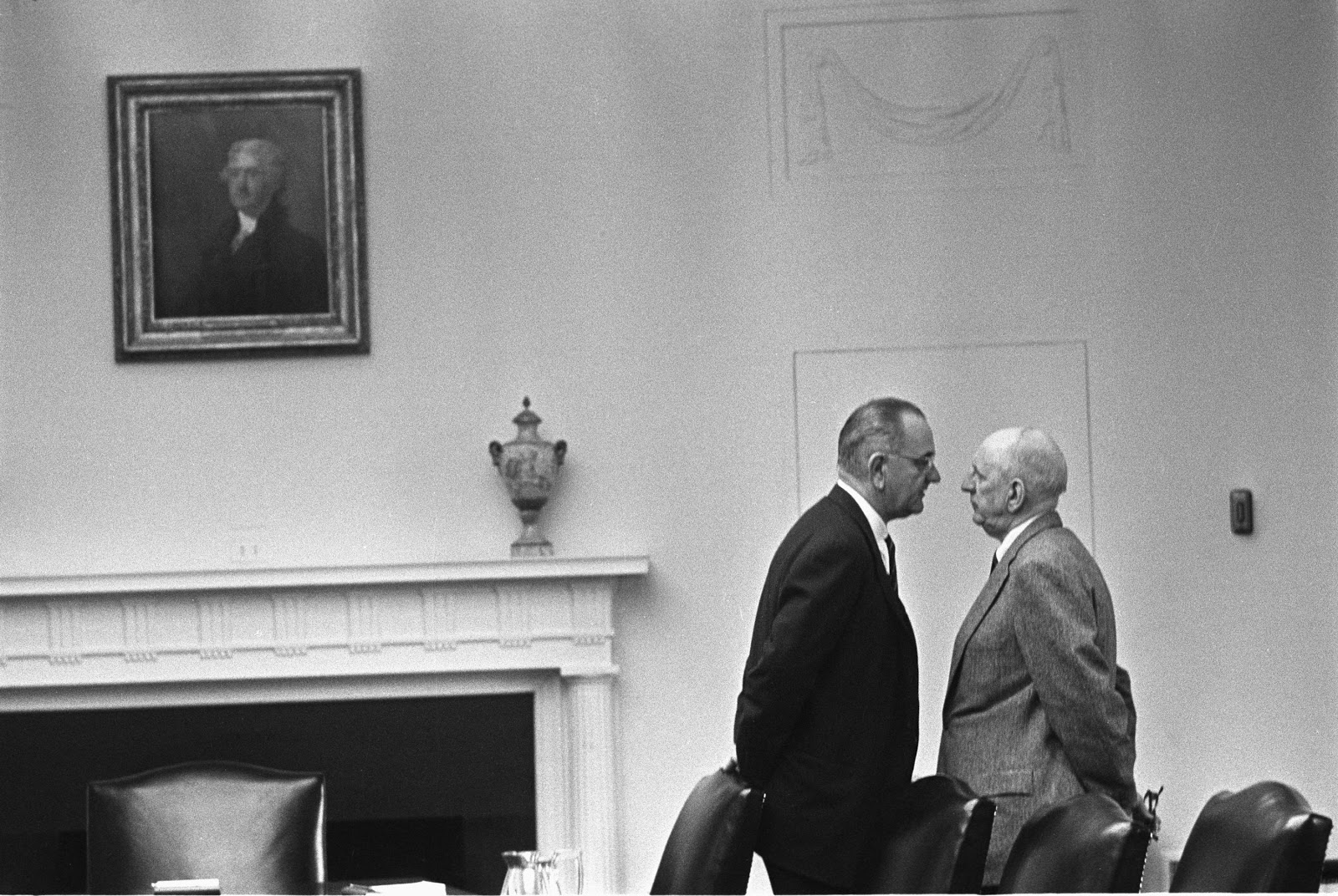

LYNDON JOHNSON AND THE GREAT SOCIETY

While the American economy suffered small downturns between 1945 and 1970, none were harsh enough to dim the hopes of Democrats that a new and “Great Society” could, and should, be built. Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) had been a young New Dealer under Franklin Roosevelt and, upon Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, quickly and ably tapped into the national sense of sympathy to pass Kennedy’s Civil Rights legislation, continue the space program and begin a raft of new legislation which he dubbed “The Great Society.” This “Great Society” included a Civil Rights Act, welfare for the poor, Medicare for the elderly, Medicaid for the poor, funds to begin community colleges, the National Endowment for the Humanities, The Wilderness Preservation Act, Water and Air Quality Acts, a minimum wage hike, a tax cut, a new Department of Transportation at the Federal level, and numerous and sundry other changes. Unfortunately for Johnson, the war in Vietnam competed for the dollars he needed for his “Great Society.” This would spawn a social revolution at home.

Lyndon Johnson, a Texan who was majority leader in the Senate before becoming Kennedy’s vice president, was a masterful politician. He had been schooled in Congress, where he developed an extraordinary ability to get things done. He excelled at pleading, cajoling, or threatening as necessary to achieve his ends. His liberal idealism was probably deeper than Kennedy’s. As president, he wanted to use his power aggressively to eliminate poverty and spread the benefits of prosperity to all.

Johnson took office determined to secure the passage of Kennedy’s legislative agenda. His immediate priorities were his predecessor’s bills to reduce taxes and guarantee civil rights. Using his skills of persuasion and calling on the legislators’ respect for the slain president, Johnson succeeded in gaining passage of both during his first year in office. The tax cuts stimulated the economy. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the most far-reaching such legislation since Reconstruction.

Johnson addressed other issues as well. By the spring of 1964, he had begun to use the name “Great Society” to describe his socio-economic program. That summer he secured passage of a federal jobs program for impoverished young people. It was the first step in what he called the “War on Poverty.” In the presidential election that November, he won a landslide victory over conservative Republican Barry Goldwater. Significantly, the 1964 election gave liberal Democrats firm control of Congress for the first time since 1938. This would enable them to pass legislation over the combined opposition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats.

The War on Poverty became the centerpiece of the administration’s Great Society program. The Office of Economic Opportunity, established in 1964, provided training for the poor and established various community-action agencies, guided by an ethic of “participatory democracy” that aimed to give the poor themselves a voice in housing, health, and education programs.

Medical care came next. Under Johnson’s leadership, Congress enacted Medicare, a health insurance program for the elderly, and Medicaid, a program providing health care assistance for the poor.

Johnson succeeded in the effort to provide more federal aid for elementary and secondary schooling, traditionally a state and local function. The measure that was enacted gave money to the states based on the number of their children from low-income families. Funds could be used to assist public- and private school children alike.

Convinced that the United States confronted an “urban crisis” characterized by declining inner cities, the Great Society architects devised a new housing act that provided rent supplements for the poor and established a Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Other legislation had an impact on many aspects of American life. Federal assistance went to artists and scholars to encourage their work. In September 1966, Johnson signed into law two transportation bills. The first provided funds to state and local governments for developing safety programs, while the other set up federal safety standards for cars and tires. The latter program reflected the efforts of a crusading young radical, Ralph Nader. In his 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile, Nader argued that automobile manufacturers were sacrificing safety features for style, and charged that faulty engineering contributed to highway fatalities.

In 1965, Congress abolished the discriminatory 1924 national-origin immigration quotas. This triggered a new wave of immigration, much of it from South and East Asia and Latin America.

The Great Society was the largest burst of legislative activity since the New Deal. But support weakened as early as 1966. Some of Johnson’s programs did not live up to expectations; many went underfunded. The urban crisis seemed, if anything, to worsen. Still, whether because of the Great Society spending or because of a strong economic upsurge, poverty did decline at least marginally during the Johnson administration.

Inner City Detroit after riots. Image from Bentley Historical Library via Vistacampus.gov

Video (00:05:27): The Presidents: Johnson (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=411643)

THE WAR IN VIETNAM

Video (00:18:55): Video: Vietnam War (Beginnings) ((https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=411643)

Before his assassination, President Kennedy had propped up the French in Vietnam against Ho’s communist insurgency. Though he did not approve of French colonialism, he was committed to containing Communism. By the time of Kennedy’s death, the Americans had 16,000 “advisors” in South Vietnam.

Dissatisfaction with Johnson’s “Great Society” came to be more than matched by unhappiness with the situation in Vietnam. A series of South Vietnamese strong men proved little more successful than Diem in mobilizing their country. The Viet Cong, insurgents supplied and coordinated from North Vietnam, gained ground in the countryside.

The French Fumble

The doctrine of “containment,” now more than a decade old, seemed to have proven itself in Greece, Turkey and Korea. It would be tested again in Vietnam. French colonizers had reasserted their authority in Vietnam after the Japanese were expelled following World War Two. Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese nationalist, wished to see all foreign control, whether Japanese, French or other, evicted from Vietnam. With Soviet support, Ho led a campaign to expel the French from Vietnam. Devastated by World War II and lacking resources, the French appealed to and received American sympathy and aid in their fight against the Communists during the second half of the 1950s.

Video (00:01:37): Extra Sadness (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/i6G7Kkd8)

As a French defeat grew increasingly more likely, Americans began taking over the military effort in an “advisory” capacity until an alleged North Vietnamese attack on two American destroyers in 1964 brought the Americans into the war in great numbers. Just as The Cold War was the driving force of American foreign policy for half a century, Vietnam became the defining event for a social revolution from which the United States has still not emerged.

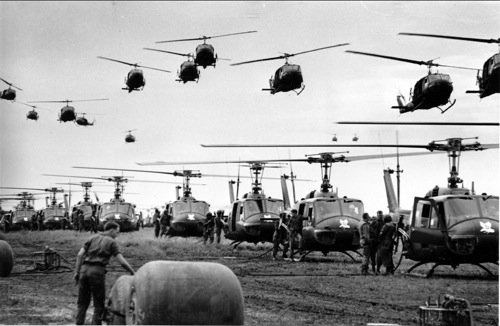

Owning Vietnam

Determined to halt Communist advances in South Vietnam, Johnson made the Vietnam War his own. After the incident with the destroyers, Johnson won from Congress on August 7, 1964, passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which allowed the president to “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.” After his re-election in November 1964, he embarked on a policy of escalation. From 25,000 troops at the start of 1965, the number of soldiers — both volunteers and draftees — rose to 500,000 by 1968. A bombing campaign wrought havoc in both North and South Vietnam.

First Televised War

Again the television would powerfully influence public opinion as the Vietnam conflict became the first-ever televised war. Americans saw nightly body counts, graphic war footage, and government officials saying that the war was being won. In 1968, the North Vietnamese planned a major infiltration of the South, to be carried out during the Chinese New Year of Tet. The “Tet Offensive” was carried out on schedule, and suddenly Americans were viewing U.S. soldiers and plainclothes C.I.A. operatives trying to retake the U.S. embassy in Saigon. Firefights erupted all over South Vietnam and were beamed into American living rooms--prompting trusted news anchor, Walter Cronkite, to ask “what the hell is going on”?

Cronkite announcing the death of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963. [Public Domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Though Tet was a massive military failure for the North (which was despondent at the initial results of their offensive), it was a huge success in turning American public opinion against the war. Tet also sank Lyndon Johnson’s ratings to below thirty percent. Johnson went on television to announce that he would not run for reelection.

Grisly television coverage with a critical edge dampened support for the war. Some Americans thought it immoral; others watched in dismay as the massive military campaign seemed to be ineffective. Large protests, especially among the young, and a mounting general public dissatisfaction pressured Johnson to begin negotiating for peace.

Video (00:01:13): The Presidents: Johnson(https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=17698&xtid=43180&loid=94122)

THE ELECTION OF 1968

By 1968 the country was in turmoil over both the Vietnam War and civil disorder, expressed in urban riots that reflected African-American anger. On March 31, 1968, the president renounced any intention of seeking another term. Just a week later, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee. John Kennedy’s younger brother, Robert, made an emotional anti-war campaign for the Democratic nomination, only to be assassinated in June.

At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, protesters fought street battles with police. A divided Democratic Party nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey, once the hero of the liberals but now seen as a Johnson loyalist. Southern white opposition to the civil rights measures of the 1960s galvanized the third-party candidacy of Alabama Governor George Wallace, a Democrat who captured his home state, Mississippi, and Arkansas, Louisiana, and Georgia, states typically carried in that era by the Democratic nominee. Republican Richard Nixon, who ran on a plan to extricate the United States from the war and to increase “law and order” at home, scored a narrow victory.

![1968 Democratic National Convention, Chicago. Sept 68 C15 1 1295 , Photo by Bea A Corson, Chicago. [Public Domain] via Wikicommons](https://www.oercommons.org/editor/images/3928)

1968 Democratic National Convention, Chicago. Sept 68 C15 1 1295 , Photo by Bea A Corson, Chicago. [Public Domain] via Wikicommons

NIXON, VIETNAM, AND THE COLD WAR

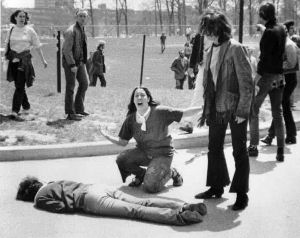

Republican Richard Nixon won the election of 1968 partly on the promise to bring an honorable end to the war in Vietnam. Determined to achieve “peace with honor,” Nixon slowly withdrew American troops while redoubling efforts to equip the South Vietnamese army to carry on the fight. Having learned as Eisenhower’s vice president that threatening nuclear escalation might bring results, he did not object when high level diplomats leaked the notion that Nixon just might use “the bomb” to end the war. Ho would not be so easily bluffed, however and drove a hard bargain. As Secretary of State Henry Kissinger shuttled to and from Paris to secure a peace agreement, Nixon authorized the bombing of supply trails in Cambodia, thus widening the war, destabilizing Cambodia and causing a new wave of student protests in American Universities. At Kent State in Ohio, the National Guard troops who had been called in to restore order panicked and killed four students.

Peace with Honor?

A peace agreement was finally reached in Paris in 1973. As the last Americans left South Vietnam in 1975, the communists swept over the countryside. The North Vietnamese carried out mass executions across South Vietnam and “boat people” (refugees fleeing South Vietnam) became regular T.V. fare as Americans watched and wondered at their first military failure.

Video (00:13:44): Nixon Fights Communism (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=8398&loid=412124)

Video (00:02:20) The Presidents: Nixon (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://digital.films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=17698&xtid=43180&loid=94123)

By the fall of 1972, however, troop strength in Vietnam was below 50,000 and the military draft, which had caused so much campus discontent, was all but dead. A ceasefire, negotiated for the United States by Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, was signed in 1973. Secretly, the administration promised to reintroduce the U.S. military campaign if the North did not hold to the ceasefire agreement.Although American troops departed, the war lingered on into the spring of 1975, when Congress cut off assistance to South Vietnam and North Vietnam consolidated its control over the entire country.

Video (00:02:50) More Sadness (https://ensemble.nmc.edu/Watch/Gn2w9ABe)

The war left Vietnam devastated, with millions maimed or killed. It also left the United States traumatized. The nation had spent over $150 billion in a losing effort that cost more than 58,000 American lives. Americans were no longer united by a widely held Cold War consensus, and became wary of further foreign entanglements.

Vietnam Consequences

Historians and diplomats are still trying to decipher the lessons of Vietnam. While the Communists were not “contained” successfully, neither did the fall of Vietnam cause the feared domino effect of southeast Asian countries falling to Marxist/Leninism. Accordingly, the doctrine of “containment” came under close scrutiny and a less rigid interpretation of “containment” emerged from the conflict. In hindsight, Ho and the North Vietnamese were beholden to neither Moscow, nor Beijing, but willingly accepted a steady stream of supplies from both.

Vietnam Syndrome

A “Vietnam Syndrome” overtook the American people who grew trigger-shy from their chastening in Vietnam. American troops would not see military action of much consequence until the highly publicized, but marginally significant invasion of Grenada in 1983, followed by a major offensive against Iraq in 1990. Perhaps the greatest consequence of Vietnam was its sapping of funds for social legislation and fueling of a social revolution at home.

Detente

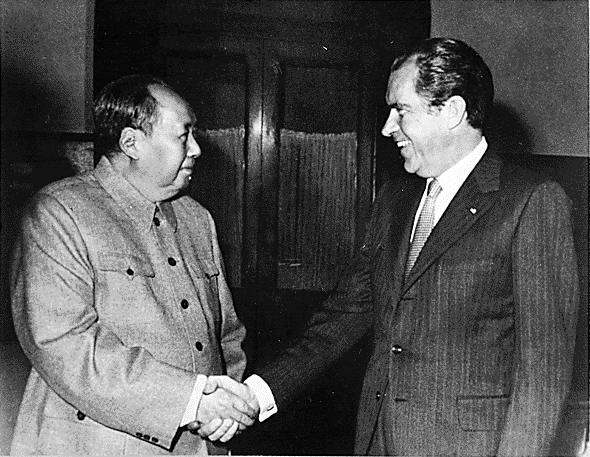

Yet as Vietnam wound down, the Nixon administration took historic steps toward closer ties with the major Communist powers. The most dramatic move was a new relationship with the People’s Republic of China. In the two decades since Mao Zedong’s victory, the United States had argued that the Nationalist government on Taiwan represented all of China. In 1971 and 1972, Nixon softened the American stance, eased trading restrictions, and became the first U.S. president ever to visit Beijing. The “Shanghai Communique” signed during that visit established a new U.S. policy: that there was one China, that Taiwan was a part of China, and that a peaceful settlement of the dispute of the question by the Chinese themselves was a U.S. interest.

With the Soviet Union, Nixon was equally successful in pursuing the policy he and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called détente. He held several cordial meetings with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in which they agreed to limit stockpiles of missiles, cooperate in space, and ease trading restrictions. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) culminated in 1972 in an arms control agreement limiting the growth of nuclear arsenals and restricting anti-ballistic missile systems.

Video (00:02:14) Nixon (Foreign Relations) (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=411660)

NIXON’S ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND DEFEATS

Vice president under Eisenhower before his unsuccessful run for the presidency in 1960, Nixon was seen as among the shrewdest of American politicians. Although Nixon subscribed to the Republican value of fiscal responsibility, he accepted a need for government’s expanded role and did not oppose the basic contours of the welfare state. He simply wanted to manage its programs better. Not opposed to African-American civil rights on principle, he was wary of large federal civil rights bureaucracies. Nonetheless, his administration vigorously enforced court orders on school desegregation even as it courted Southern white voters.

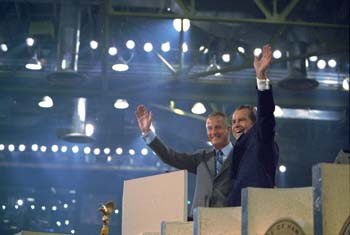

Perhaps his biggest domestic problem was the economy. He inherited both a slowdown from its Vietnam peak under Johnson, and a continuing inflationary surge that had been a by-product of the war. He dealt with the first by becoming the first Republican president to endorse deficit spending as a way to stimulate the economy; the second by imposing wage and price controls, a policy in which the Right had no long-term faith, in 1971. In the short run, these decisions stabilized the economy and established favorable conditions for Nixon’s re-election in 1972. He won an overwhelming victory over peace-minded Democratic Senator George McGovern.

Watergate

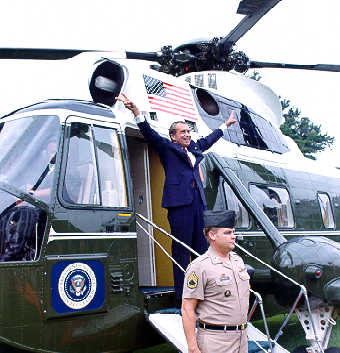

Things began to sour very quickly into the president’s second term. Very early on, he faced charges that his Committee to Reelect the President (CREEP) had managed a break-in at the Watergate building — headquarters of the Democratic National Committee— and that he had participated in a cover-up. Special prosecutors and congressional committees dogged his presidency thereafter. The Watergate burglary in 1972, in which President Nixon was now implicated, ruined Nixon’s presidency and forced his resignation in August of 1974.

OPEC

Factors beyond Nixon’s control undermined his economic policies. In 1973 the war between Israel and Egypt and Syria prompted Saudi Arabia to embargo oil shipments to Israel’s ally, the United States. Other member nations of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) quadrupled their prices. Americans faced both shortages, exacerbated in the view of many by over-regulation of distribution, and rapidly rising prices. Even when the embargo ended the next year, prices remained high and affected all areas of American economic life: In 1974, inflation reached 12 percent, causing disruptions that led to even higher unemployment rates. The unprecedented economic boom America had enjoyed since 1948 was grinding to a halt.

Nixon Crashes

Nixon’s rhetoric about the need for “law and order” in the face of rising crime rates, increased drug use, and more permissive views about sex resonated with more Americans than not. But this concern was insufficient to quell concerns about the Watergate break-in and the economy. Seeking to energize and enlarge his own political constituency, Nixon lashed out at demonstrators, attacked the press for distorted coverage, and sought to silence his opponents. Instead, he left an unfavorable impression with many who saw him on television and perceived him as unstable. Adding to Nixon’s troubles, Vice President Spiro Agnew, his outspoken point man against the media and liberals, was forced to resign in 1973, pleading “no contest” to a criminal charge of tax evasion.

Nixon probably had not known in advance of the Watergate burglary, but he had tried to cover it up, and had lied to the American people about it. Evidence of his involvement mounted. On July 27, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee voted to recommend his impeachment. Facing certain ouster from office, he resigned on August 9, 1974.

Video (00:02:10)The Presidents: Nixon (Legacy) (https://login.proxy.nmc.edu/login?url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=105019&xtid=43180&loid=411661)